Haere mai and welcome to the third blog in our ‘Te Whare Tapere to Kapa Haka and Māori Concert Party’ series. You can find Part One, and Part Two here.

Haere mai and welcome to the third blog in our ‘Te Whare Tapere to Kapa Haka and Māori Concert Party’ series. You can find Part One, and Part Two here.

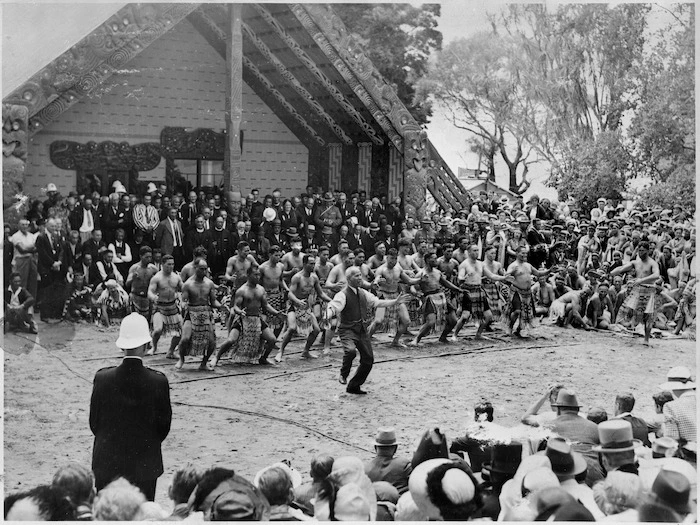

The modern kapa haka competitions began around the time of the first Waitangi Day celebrations in 1934:

Ngapuhi performance at Waitangi, 1934 — NZHistory.net

The Polynesian Festivals were held at Rotorua, 1972 and 1976. Regional teams took part, but also present were Pacific rōpū until 1983 when the festivals became the Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Festival.

In 1976, rōpū representing Guam and Australia attended the festival. Guam had become an unincorporated territory of USA in August 1950, and its contribution to the festival revealed an almost complete annihilation of the indigenous culture. The rōpū’s waiata-ā-ringa including the shooting down of Japanese invader planes (30 years after the end of WWII), and the singing of the current USA pop song (in English) of ‘How much is that doggie in the window’.

The Aboriginal rōpū told their stories in dramatic role plays backed by their instruments such as didgeridoo — they didn’t stand in kapa / lines for their cultural performances at all.

The Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Festival existed between 1983 and 2004.

Have watch of the Iwi Anthems television programme, which began screening on Māori Television in 2013:

Every iwi has an anthem, they are the waiata and haka we love to perform at gatherings. Our iwi anthems tell unique stories about our tribes revealing who we are and what’s important to us.

The competitions rotated from marae to marae setting, with tribal influences dominant in each iwi/hapū territory. The iwi anthems became signature tunes for the respective iwi, with perpetuation of dialect specific to their region. With the influence of migrations to urban centres in search of jobs and upskilling (by trade training, nursing, etc) there was a move to pan-tribal rōpū with pan-tribal influences for members, composers, tutors.

Watch a video from Te Ara of Kapa haka group Te Waka Huia performing the whakaeke (entrance) at the 1996 Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Festival:

Te Rita Papesch has written an overview of those years in the book: The state of the Māori nation : twenty-first-century issues in Aotearoa, published in 2006:

“Kapa Haka” — Chapter 2 in State of the Māori nation : twenty-first-century issues in Aotearoa

“Dealing with a diverse range of issues that affect Maori living in modern-day New Zealand, State of the Maori Nation is a collection of 22 short and informative essays drawn from Maori commentators, historians, teachers, researchers and academics working across the country in all manner of industries. This is a book with something for everyone — Maori and Pakeha, men and women, young and old — and gives a vision of a confident and capable people moving from strength to strength within every aspect of contemporary New Zealand society. The subjects covered in the book include: kapa haka […]” (Catalogue)

Te Matatini was formed in 2004, and the competition has now moved to a handful of centralised city settings – influenced by underlying economic factors such as the large size of the moveable stage, and the cost of hosting the competitions. But there has also, lately, been a return to the telling of tribal stories alongside themes of world-wide concerns.

Te Matatini performances have become dramatic, passionate, fluid, and topical in the stories they bring to the stage, but the staunch tutors and leaders of the kapa haka teams declare the centre of Kapa Haka lies, and must always lie, with the care and attention to the reo within these cultural performances, even where a regimented “correct” body poses of the past ideals are no longer of paramount importance.

Watch Hikurangi‘s Te Matatini performance in 2019. Here is the signature waiata of Ngāti Porou – where the rangi and costumes honour the legacy of Te Moana-nui-a-kiwa Ngarimu, but the actions, foot, arm, hip movements are vigorous, “lively” and far from “traditional”:

Hikurangi’s kapa haka legacy continues — Article and video

“Aspiring to preserve the waiata, traditions and legacy of their kapa, Hikurangi is one of the longest-standing kapa in the country, having been established in 1934.”

Further books from our shelves:

Haka : te tohu o te whenua rangatira = the dance of a noble people / Kāretu, T. S. (1993)

Timoti Karetu describes the various types of haka and their different roles in Māori customs.

Mātāmua ko te kupu! : te haka tēnā! te wana, taku ihi e, pupuritia / Kāretu, T. S. (2020)

“[Sir Tīmoti Kāretu] is also an unrivalled creator of waiata and haka, composing songs and judging at Te Matatini and other events. In this book, Sir Timoti shares his extensive experience in the artforms of haka and waiata – from Maori songs of the two world wars to the rise of kapa haka competitions, from love songs to action songs, from Sir Apirana Ngata to Te Puea Herangi, and from Te Matatini to contemporary hui on marae.” (Catalogue)

Kia Rōnaki = The Māori performing arts

“In the last thirty years there has been an explosion of interest in the Māori performing arts but until now there has been no general book written in English or Māori about the Māori performing arts by Māori authors and exponents of the various genres. This new work, Kia Rōnaki: The Māori Performing Arts, edited by John Moorfield, Tania Ka’ai and Rachael Ka’ai-Mahuta, brings together the expertise of a range of performance artists and academics, consolidating their knowledge into a comprehensive single volume that will be of relevance to all those interested in the Māori performing arts.” (Catalogue)

Haka : a living tradition / Gardiner, Wira

Chapter “Kapa Haka as a web of cultural meanings” by Hector Kaiwai, in Cultural studies in Aotearoa New Zealand : identity, space and place

Kapa haka mai rānō ki tēnei wā, has been important to iwi on several levels — as a driver of perfection in te reo, as a way of carrying through stories pūrākau and traditions of the past, and now, as a way of raising awareness of current local and global issues.

Kia kaha te reo Māori — mō āke tonu atu.

Read more:

“Taunaha Whenua: Naming the Land”

“Taunaha Whenua: Naming the Land” “Memorials, Names and Ethical Remembering”

“Memorials, Names and Ethical Remembering”