For much of the 20th century, entertainment in Wellington was dominated by movies and movie theatres. Many of our early cinemas grew or were adapted from live theatres following the first screening of ‘motion pictures’ in the capital city in 1896.

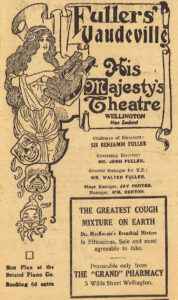

For the next decade, short films of around two to four minutes in length often became a part of local vaudeville shows where they would appear on a programme of entertainment along with live song and dance routines, magicians, jugglers and trained animal acts. Interest in the new medium increased with the onset of the Boer War, with people clamouring to see footage of “our boys” in South Africa which followed the filming of troop departures from Wellington in 1900 (the oldest surviving film footage to be shot in New Zealand). Films also began to be shown in the Wellington Town Hall, as well as various community and church halls, but a new era began in 1910 when the Kings Theatre opened in Dixon Street as New Zealand’s first purpose-built cinema. Four years later it became the venue for the Wellington screenings of Hinemoa, New Zealand’s first (silent) feature film, with a musical accompaniment provided by the cinema’s own in-house orchestra. Though movies remained popular during the First World War, the conflict saw a resurgence in more community-focussed entertainment such as rallies, dances and mass-singing events. Restrictions on the supply of building materials during the war saw a halt to most cinema construction (the only significant theatre to open during this time was the Paramount in Courtenay Place in 1917), but the inter-war period which followed was to become the ‘Golden Age’ of movie theatres.