Recently I breathed in the gentle gentility of the Wellington Club, The Terrace, whilst held in awe of Helen Riddiford’s meticulous and deeply researched account of the New Zealand Company’s finest member, Dr George Samuel Evans.

By evening’s end, there were surely more than the just the two of us who would attest to his right to be named Wellington’s founding father, – a man who stood tall on the principles and the application of the Company’s constitution and held a desire to include tangata whenua in te ao hurihuri, / an evolving new life. In the words of one of our two official languages – here was a man truly worthy of the description: he kōtuku rerenga tahi.

By evening’s end, there were surely more than the just the two of us who would attest to his right to be named Wellington’s founding father, – a man who stood tall on the principles and the application of the Company’s constitution and held a desire to include tangata whenua in te ao hurihuri, / an evolving new life. In the words of one of our two official languages – here was a man truly worthy of the description: he kōtuku rerenga tahi.

For all the sentiments expressed above – how many people , today, remember any details of this man who gave his name to that inner bay (Evans’s / Evans Bay) and whose contribution to the settlement placed him second only to Colonel Wakefield, in his roles, which included that of chief judicial authority for the new colony.

When Edward Gibbon Wakefield accompanied Lord Durham to Canada, it was Dr Evans who stepped forward to place his hand firmly on the tiller of the colonial ship.

But who was this man? George Evans grew up in a household where civil and religious liberty was embraced. He was a brilliant scholar who excelled in Latin, Greek and Hebrew – His later work spanned the fields of education, judiciary and journalism. In 1928 he became, briefly, headmaster of Mill Hill School, London.

(Source: School House at Mill Hill School : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mill_Hill_School)

It was here that he met school matron Mrs Riddiford, whose husband passed away in 1829. George and Harriet married, 16 January 1930, and George became the stepfather of Amelia (13 years) and Daniel (16 years) – he, Daniel, who was to become the founder of the Riddiford farming dynasty at Orongorongo and the stations around the Wairarapa coast of New Zealand.

There is so much detail of Evans’ life within the pages of this book. There’s the interesting story of his involvement with Nayti and Hiakai, two passengers on the Mississippi who became stranded at Le Havre, were rescued by the New Zealand Association and provided with lodgings by Wakefield and Evans, in the 1830s. With Hiakai’s help George Evans was introduced to Māori customs and reo. He began a grammar of Te Reo Māori, which was completed in 1839, but never officially published. Wellington City Central Library holds a copy of this Manuscript of a Maori grammar.

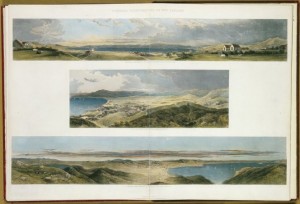

The top view stretches across Thorndon Flat with Dr Evans’ house on the left, a range of early houses and businesses along the waterfront and on the right, Colonel William Wakefield’s house with flagpole.

(Source: Brees, Samuel Charles, 1810-1865 :Pictorial Illustrations of New Zealand. London, John Williams and Co., Library of Arts, 141, Strand, 1847.. Ref: PUBL-0020-22. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22816178)

Dr Evans fulfilled a designated role as advocate for Māori in all legal disputes – with varying degrees of success. Helen’s easy- read documentation of Dr Evans life and work in the new colony makes this book an absolute must for those of us mindful of the view – that you must first understand and embrace the past in order to move forward.

The study of the settlement of Wellington is a very complex exercise – but – don’t be confined only to those official publications — the reports and commissions, and records of deeds of release – Here lies, within these pages, the flavour of that era. This is a far more interesting journey by way of Helen’s archival research and her detailed account of Dr Evans work.

Dr Evans returned to England, 1846-52, and was dealt to harshly by the Company, in clearing the debts on his town and country sections in Wellington. It was an example of Wakefield’s ‘ability’ to turn against his closest allies.

George Evans and Harriet moved to Melbourne, 1853. He planned to undertake legal work but also began working with the Melbourne Morning Herald. He later gained a seat in the legislative assembly. His journalistic output was legendary. George and Harriet returned to New Zealand, 1865, but Harriet died 31 March 1866, and Dr Evans’ death followed in 1868.

In the words of Helen Riddiford “In the colonies he was head and shoulders above many of his peers in education and ability. He operated within an influential network of men, but was always independent in his views, which isolated him from many of his contemporaries. He was viewed as a ‘singular character’ a gentleman almost unique in this setting. His many visionary ideas were handicapped by a volatile temperament and principles that were compromised by circumstances, an unpredictable man of reckless courage whose steadfast commitment to the creation and success of Wellington was fully acknowledged after his death. Amongst others, The Independent noted that he was ‘one of the founders, if not the real founder of this colony. There is scarcely an official document of the period in which [his] name is not conspicuous”.

Here was a man truly worthy of the title bestowed by his Māori friends – Nui, Nui Rangatira