Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna - The Path of our Ancestors

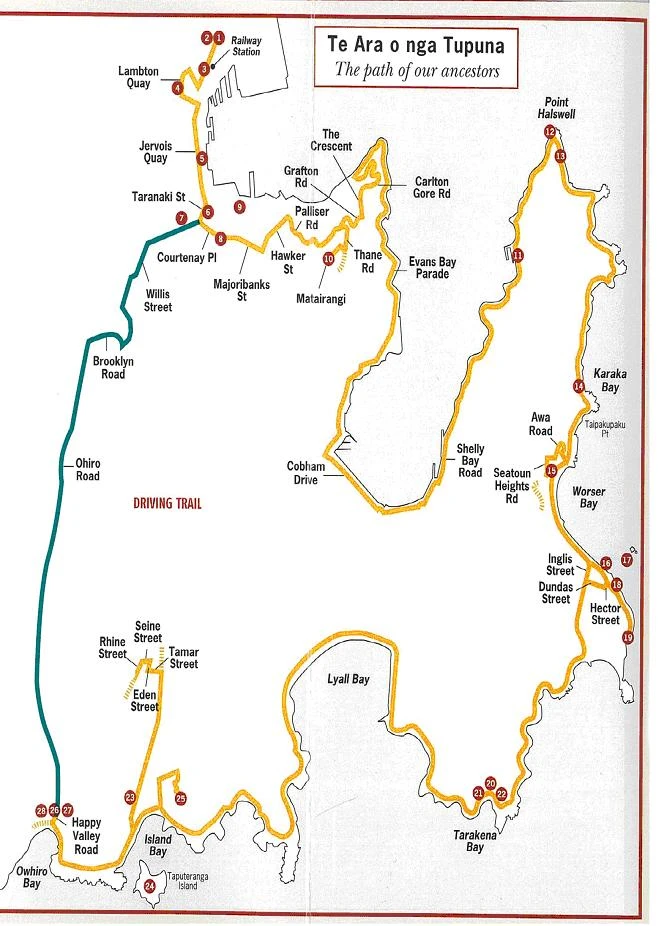

Te Ara o Ngā Tūpuna (The Path of Our Ancestors) heritage trail, from Thorndon to Owhiro Bay. A joint project between Wellington City Council, the Wellington Tenths Trust and Ngati Toa.

I te reo Māori -

Ka Patua te whenua i te kino

Ka ngaro te mana me

te wairua mo te iwi

Mēnā ka āta haere koe i tēnei ara, e whā haora pea te roa o te taraiwa me te tirotiro haere. E taea ana te nuinga o ngā wāhi tirohanga pai e ngā turu tūroro engari kei ētahi wāhi o te makatea, he kaupae kē, arā, kei ngā pā o Rangitatau me Uruhau ētahi.

Ka tū he pou whakairo ki ētahi wāhi o te ara hei tohu i ngā papanga.

Ahakoa e mōhiotia ana e ētahi o ngā kaitirotiro, kua tanumi ki tua kē ngā papanga i nōhia e te Māori o neherā, kei te mau tonu te wairua ki ēnei wāhi.

Ko ētahi tonu o ngā papanga o tēnei makatea, he hou kē te hoahoatanga o ngā whare - pērā i te marae o Pipitea me te marae o Tapu Te Ranga e kitea ai ngā papanga Māori mai i ngā wā rerekē o ngā tau kua pahure.

Ngā āhuatanga o te Ara

Ka tīmata te makatea i te marae o Pipitea, i Thorndon Quay, e noho koaro mai ana i te teihana rerewē, ā, ka haere tae noa ki te whanga o ōwhiro, i te taitonga o Pōneke. Kāore e uru te katoa o ngā pā, ngā kāinga, ngā marae me ngā urupā ki roto i tēnei makatea, engari ko ngā papanga o roto, i kōwhiritia nā te mea he wāhi whakahirahira nō Pōneke.

Ahakoa ko te tikanga o tēnei makatea, he ara taraiwa kē, he nui tonu ngā wāhi hīkoikoi, kia kitea ai ētahi tirohanga pai rawa atu o Pōneke. (ake i te Whanganui-a-Tara me te taitonga)

Ngā Kōrero a Ngā Tūpuna

Ko te ingoa tawhito o Pōneke, ko "Te Upoko o te Ika a Maui." Arā, mō te māhunga o te ika i hīia ake e te tipuna whakatere waka, a Maui, ā, i tapaina nei hoki taua ika - ko Te Ika a Maui.

Ko Kupe (he nui ngā wāhl e pā ana ki a ia) rāua ko Ngahue, ngā tāngata tuatahi ki te noho i te tonga o te whanga, ki Maraenui i te tau 925 AD.

Nō muri mai ko ngā tama a Whātonga, arā, ko Tara rāua ko Tautoke, i ahu mai i Te Māhia. Nā runga i ā rāua kōrero pai mō te wāhi nei, ka nōhia te rohe o Pōneke e Whātonga mā. Nā reira ka mōhiotia ai te rohe nei ko "Te Whanganui-a-Tara." Koinei tonu tētahi o ngā ingoa nui a te Māori mō Pōneke.

He nui tonu ngā wāhi o Pōneke i tū ai ngā pā o ēnei tāngata, arā a Motukairangi, kei reira ngā pā tūwatawata o Te Whetū Kairangi me Rangitatau. I te rautau tekau mā whitu, he pā rongonui a Rangitatau, i te wā i nohia ai e Tūteremoana. I moe tana tamāhine a Moeteao i tētahi rangatira o Ngāi Tara, o Heretaunga, ā, nā tēnei moenga i kaha ai te moe tahi a Ngāi Tara rāua ko Ngāti Ira. I ēnei rā ka noho te rahi o Ngāi Tara i raro i te ingoa o Ngāti Ira.

Nō muri mai ka hono atu a Ngāti Kahungunu rātou ko Ngāi Tahu me Ngāti Māmoe ki a Ngāti Ira. He wāhi atu tō tēnā iwi, tō tēnā iwi, i mua i te wehenga o Ngāi Tahu me Ngāti Māmoe ki te Waipounamu, i ngā rautau tekau mā ono, tekau mā whitu rānei.

I te tau 1819 i ekengia a Pōneke e ngā ope taua o Taranaki, o ātiawa, o Ngāti Toa, o Ngā Puhi me Ngāti Whātua. Hinga katoa ana ngā pā tūwatawata nui o Ngāti Ira. Ka rere te nuinga o Ngāti Ira ki Te Wairarapa, ā, e noho tonu ana rātou ki reira i ēnei rā.

I ngā tau 1825-26 ka neke mai ko Ngāti Tama rātou ko Ngāti Mutunga me Te ātiawa o Taranaki iwi, ki Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Ka whakatū kāinga rātou ki te wāhi o te tāone pū o Pōneke, o te ākau o Petone me Te Awakairangi. I noho tonu te taha rāwhiti o te whanga ki raro i te mana o Ngāti Ira rāua ko Ngāti Kahungunu.

Kāore i pai te noho a ngā iwi nei me ngā iwi o Taranaki, ā ka tae ki te wā ka whakaekengia a Ngāti Ira rāua ko Ngāti Kahungunu e Taranaki, ā, ka panaia atu ki Te Wairarapa. Ka noho te mana o te whanga me ngā whenua katoa e karapoti ana ki a rātou.

I tua atu i ngā mōrehu o ngā iwi i noho ki konei i mua, he maha tonu ngā iwi puta noa i te motu kua noho ki Pōneke mai I ngā tau 1960. Nā tēnei kua puta tētahi āhua ahurei me te hanumi e pā ana ki ngā iwi o te rohe o Pōneke.

Nā runga i tēnei mea te "ahi kā" me te "ōhākī," ko Te āti Awa te tangata whenua o Pōneke.

Te Tīmatatanga o te Makatea -

Ka tīmata i te marae o Pipitea i Thorndon Quay. Mai i konei ka kitea atu te marae o Pipitea, te wāhi o te pā o Pipitea (papanga 2) me te ākau tawhito.

1. Te Marae o Pipitea.

I waihangatia tēnei marae hou i ngā tau tīmatanga o 1980, hei whakaruruhau mō ngā iwi Māori e noho ana i te rohe o Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Kua tohua hei wāhi tūtakitaki mō ngā iwi katoa ahakoa ko wai, i raro i ngā tikanga Māori. Koinei te marae nui rawa atu o Pōneke, ā, nā tana tū hei marae tāone, he nui tonu ngā wā, ka whakamahia hei wāhi hui, hei wāhi whakaaturanga.

Ko te papa whenua o runga ake o te marae te wāhi o te pā o Pipitea.

2. Te Pā o Pipitea

He wāhi whakahirahira tēnei ki ngā Māori o Pōneke. He kāinga tūturu te pā o Pipitea, e titiro whānui ana ki te ākau, e tū pātata ana ki te wai māori me ngā māra kai. Ahakoa te pai o taua wāhi mō ngā urunga waka, he wāhi tūwhera ki ngā ope taua e heke mai ana i te raki. He poto hoki te wā ki te whakahiwa i ngā tāngata o te pā mehemea he waka taua e uru mai ana ki te whanga.

Ko Ngāti Mutunga, i heke whakatetonga mai i Taranaki i roto i te hekenga nui o te Nihoputu i te tau 1824, ngā tuatahi ki te wāhi nei. Ko Patukawenga rāua ko Te Poki ngā rangatira o Ngāti Mutunga i Pipitea i te tau 1835, ā, i taua wā ka papare rātou i tō rātou nā mana whenua ki te wāhi nei, ki a Te āti Awa, kātahi rātou ka rere ki Reikohu.

āhua 2.5 heketea te rahi o te pā o Pipitea, ā, he nui tonu ngā māra e karapoti ana i te pā. Ko tōna rohe takiwā kei waenga i ngā tiriti o Davis, o Pipitea me Mulgrave, ā, e waru tekau ngā tāngata e noho ana i reira i ngā tau 1840. I kerēmetia te nuinga o te wāhi nei e ngā Pākeha me te hokonga a te Kamupene o Aotearoa i te tau 1839. Kei te haere tonu ngā whakahē mō tēnei take i ēnei rā tonu.

Te ākau Tawhito

I mua, arā kē te ākau e noho ana, arā, i te tiriti i te taha tonu o te marae o Pipitea (mō ngā kōrero ake e pā ana ki te ākau, me huri ki te puka iti "Old Shoreline" Heritage Trail)

Kua rerekē te ākau o Pōneke mai i te tīmatanga o te noho a te Pākeha i ngā tau 1840,. I aua rā he one noa iho, ā, tae noa ki te wā i tū ai ngā wāpu. Koira anake te wāhi i taea te whakatau atu mai i te moana. 155 heketea te rahi o te wāhi i whakawhenuatia hei whakawhānui i te tāone pū, ā, nā tēnei i tino rerekē ai te āhua o te whanga, otirā, nā tēnei hoki i ngaro atu ai ngā kai mātaitai me ngā whata kai.

Haere whakatetonga mā Thorndon Quay, hipa atu i te teihana rerewē ka huri ki te taha matau, ki te tiriti o Whitmore. I Lambton Quay, me huri taha mauī, kātahi ka tū ki te pito o Woodward Street.

3. Kumutoto Kāinga

I tū te kāinga o Kumutoto ki te tahi hauāuru o te tiriti o Woodward, i runga ake o te waha o te awa o Kumutoto, ā, i rere ki te moana i te whakawhitinga o ngā tiriti o Woodward me Lambton Quay. (Ka rere te awa o Kumutoto mā raro i te whenua i naianei, kātahi ka puta ki te moana).

I mōhiotia tēnei wāhi nā te mea he wāhi rauhi harakeke. He wāhi pai mō te ūnga waka, ā, i te tau 1831, i whakamahia te wāhi nei hei pokapū kohikohi mō ngā teihana harakeke, e tū tū haere ana i te taha rāwhiti o Te Ika a Maui. Nā tōna kaha, i pīrangitia te taonga hoko nei, te harakeke, e te Pākehā o taua wā, nā te mea he nui ōna whakamahinga hei taputapu noa o ngā wā katoa, pērā i ngā taura mō ngā kaipuke, ā, mō te here me te rauwhare i ngā whare me ngā tuanui.

I mua, koinei te kāinga o te rangatira o Te ātiawa, a Wi Tako Ngātata me ngā tāngata e 50, i neke ki reira i te wehenga atu o Ngāti Mutunga ki Rerekohu i te tau 1835.

I mutu te tū o tēnei kāinga hei kāinga noho i te wā i neke atu ai a Wi Tako ki Te Awakairangi.

Haere mā Lambton Quay ka huri mauī ki te tiriti o Johnston. Huri matau ki te tiriti o Jervois ka whai i te tiriti ki te tiriti o Taranaki ki tōna pūtahitanga me Courtenay Place. Kei te taha matau ko te pāka o Te Aro. Kimihia te tohu kei runga i te whakamaharatanga kōhatu kei te pāka o Te Aro.

4. Te Kāinga o Te Aro

I waihangatia te kāinga o Te Aro e Ngāti Mutunga i te tau 1824. Nō tō rātou haerenga atu, ka weheruatia te kāinga, ā, āhua 35 ngā tāngata o Ngāti Ruanui i te taha rāwhiti e noho ana, ā, i te taha hauāuru, 93 o te iwi o Ngāti Haumia rāua ko Ngāti Tūpaia o Taranaki e noho ana.

Ko Waimāpihi te ingoa o tētahi awa e rere tata ana ki a rātou He pātaka kai nui mō ngā Māori, ā, i whakaingoatia mō te wāhi kaukau o tētahi puhi, a Māpihi,

I pōhiritia ngā mihinare Wēteriana, a Bumby, rātou ko Hobbs me Minarapa Rangihatuaka i Te Aro, ā, i hoatunā hoki he whenua hei hanga whare karakia mō rātou. Ka rāhuitia e ngā mihinare rā te pā me ngā whenua noho pātata kia kaua e hokona atu. Tae noa ki te marama o Hui-tanguru i te tau 1844 kāore ngā Māori o Te Aro i whakaae kia hokona atu ō rātou whenua ki te Kamupene o Aotearoa. Engari, i te mutunga o te tau 1844, i hainatia e ngā rangatira tokoono o te kāinga nei te whakaaetanga ā-pepa, tuku ai i a Te Aro, ki raro i te hokonga a Te Kamupene o Aotearoa o te tau 1839.

Nā tētahi rū whenua i te tau 1855 i hiki te whenua i Te Aro, ā, ka heke iho te wai. Nō mua, he pātaka kai taua wāhi, arā he mātaitai i ngā wāhi pāpaku, he tuna i ngā repo, ā, he nui hoki te harakeke e tipu ana. He kaha te hiahia o tauiwi ki te harakeke. Nā te ngaronga o ngā kai me te kore tumu ōhanga, tāpiri atu ko ngā mate e kaha pēhi ana, me te hokinga nui ki Taranaki i te tau 1860 ki te whakatau i ngā raruraru whenua, i heke ai te noho o ngā tāngata ki te pā o Te Aro, ā, tae noa ki te tau 1870 ka hokona te nuinga o ngā whenua e toe ana hei whāroa ake i te tiriti o Taranaki, tae noa ki te moana.

Haere rāwhiti mā te tiriti o Courtenay ka tū ki tōna mutunga. Ko te repo o Waitangi kei te pūtahitanga o ngā tiriti o Courtenay me Cambridge.

5. Te Repo o Waitangi

He pātaka kai anō te repo o Waitangi nō Ngāti Ruanui me Ngāti Haumia hapū. E ai ki ngā kōrero, he taniwha e noho ana i taua repo, engari nā tana mōhio ki a tauiwi e taetae mai ana, ka whakawāteatia e ia te repo i mua o tō rātou taenga mai.

Me taraiwa ki runga o Matairangi mā te tiriti o Majoribanks (tiro ki te mahere whenua). Tae atu ana ki te tūnga waka, pikitia te ara ki te taumata o Matairangi kia kite ai koe i tētahi tirohanga mīharo o Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Kimihia te tohu kōrero kei reira.

6. Tangi- te-Keo (Te taumata o Matairangi)

Mai i konei ka kitea te nuinga o te whanga o Pōneke. E ai ki ngā kōrero o neherā he taniwha e noho ana i roto i te whanga nei. (I taua wā hoki, he roto kē te whanga). Ko tētahi o ngā taniwha nei, arā, a Ngake, he taniwha okeoke, he taniwha tūkaha, ā, ko tōna tino hiahia, kia puta ia i tana here - ki te moana. Tere tonu tana rere ki te kokonga karepū o te whanga, ki reira takawiri ai i tana whiore ki te whakapipi haere i te wāhi pāpaku (ko Waiwhetū tērā), kātahi ia ka rara ake, ka rere ki ngā toka e karapoti ana i te roto, ka tūkia atu, ā, puta noa ia ki Raukawa moana.

Ko tērā o ngā taniwha, a Whātaitai, i whakaaro kē kia puta mā tētahi atu putanga. Kātahi ka panaia e ia tana whiore, ā, ko te tāwhārua o Ngaūranga tērā. Ka haere a Whātaitai mā tērā taha o te Motu Kairangi, i reira raru ai i te tai timu, me te tai pari i tukuna atu e Ngake. Nā reira i riro ai te wāhi rā hei kūititanga ki waenganui i Motu Kairangi me te taha uru o te whanga, ā, koirā te taunga waka rererangi i naianei. E ai ki ngā kōrero, ko Tangi-te-keo te wairua o Whātaitai, i rere manu atu ai ki runga o Matairangi, ki reira tangi ai.

Mai i konei ka taea hoki te kite atu i ngā motu, a Matiu (Somes) rāua ko Makaro (Ward). Nā Kupe i whakaingoa, ā, he wāhi pai hei whakaruru. He wāhi punanga a Matiu rāua ko Makaro, engari nā te kore wai o reira, i kore nohia ai mō te wā roa, ā, kāore i whakatūria he hanganga i konei.

Whāia te tiriti mai i Tangi-te-keo ki Oriental Parade, kātahi ka huri matau. Whāia te taha moana o Pt Halswell (tirohia te mahere). Ka taea te kite atu a Rukutoa, a Pt Halswell me Motu Kairangi i te taha mauī.

7. Rukutoa

Ko Rukutoa te wāhi moana e kitea atu ana mai i te tīramaroa. He wāhi nui tēnei mō te hī ika me te kohi mātaitai mō ngā iwi o roto o te whanga. I tapaina tēnei ingoa nā te mea ko ngā toa anake ki te rukuruku ngā mea e āhei ana ki te ruku i reira, nā te kaha o ngā ia tai me te wai pokepoke. He maha tonu ngā tāngata kua mate i konei.

Haere tonu mā te ākau ka tū ki te tūnga waka, ka hipa ana koe i te kūrae.

8. Kai Whakaaua Waru Kainga

Kei te taha rāwhiti o Point Halswell tētahi kāinga i nohia e Ngāti Ira, ko Kai Whakaaua Waru te ingoa. He māra kai i te taha o te kāinga nei, me tētahi awa e rere ana. E ai ki tētahi kaituhi, he nui tonu ngā ahu otaota me ngā kōhatu hāngi e putu ana i te wāhi rā, ā, tērā pea he māra kūmara e tata ana i reira.

Haere tonu mā te ākau o Pt Taipakupaku. Kimihia te wāhi whakangā kei te taha mauī o Pt Taipakupaku (hipa atu i te tiriti), ā, kei reira e tū ana ētahi kāinga e ono i runga i tētahi urupā tawhito.

9 Taipakupaku Pt : Papanga Urupā

He nui tonu ngā tūpāpaku mai i ngā tau kua kitea i te wāhi nei, tae noa ki ngā anga kōiwi me tētahi upoko e nohotū ana i te rua. He nui ake ngā taonga kua kitea, tae noa ki tētahi pounamu kua tīmata te kauoro. He maha tonu ngā iwi i noho i te wāhi nei i ngā tau tīmatanga o ngā tau 1800.

Haere tonu mā te tiriti o te ākau ka huri matau ki te tiriti o Awa. I te taumata o te puke me huri mauī ki te tiriti o Seatoun Heights. E tū koe ki te wāhi tirohanga o Seatoun Heights.

10. Te Pā o Whetū Kairangi

Nā Tara tēnei pā i waihanga i tō rātou taenga tuatahi mai ki konei noho ai. E tohu ana te ingoa o te pā nei ki ngā whetū i te rangi, ahakoa te mea, e rua kē ngā kōrero mō te ahunga mai o te ingoa nei. Ko tētahi o ngā kōrero - he kore nō ngā tangata o te pā e kite kāinga i tua atu i ō rātou, ko ngā whetū anake. Ko te kōrero tuarua, i whakaingoatia te pā nā te mea, ki te titiro ki taua pā mai i te ākau, ka whakaarotia he whetū kē ngā ahi e muramura mai ana.

E āraitia ana tēnei pā mai i ngā ope taua ohorere e ngā pā o waho ake, ā, he whakaruru hoki tēnei mō ngā tāngata o ngā kāinga noho tata ki te pā. Kāore i tawhiti ake, ko te pā iti o Kākāriki-Hutia, kei te tokerau o te ranga. I whiwhi tēnei pā i tana ingoa nā tētahi rangatira o te pā, i te wā, i tū he pakanga, ā, ka kapohia atu e ia tētahi Kākāriki kāore anō i tunua, kātahi ka kainga e ia, i a ia e oma ana ki te whawhai. Ka toa rā te rangatira nei, ā, ka kīia nā ngā manu mata i kainga rā e ia, i toa ai.

I nōhia te pā nei o Ngāti Ira mō te wā poto e tētahi o ngā kaiwhai a Wi Tako Ngātata, o Te ātiawa, i mua i tō rātou haerenga ki te pā o Kumutoto noho ai i ngā tau mutunga o 1830.

Hoki atu ki te tiriti ākau, ka haere ki Seatoun. Whāia te Marine Parade ki tōna mutunga, ka huri taha matau ki te tiriti o Inglis, kātahi ka huri mauī ki te tiriti o Dundas. Me huri taha mauī ki te tiriti o Hector, kātahi ka tū ki te taha o te pāka.

E tohu ana tēnei pou i te wāhi i ū tuatahi mai a Kupe, arā, Te Tūranga o Kupe (11), Te Aroaro-o-Kupe (12) me Kirikiri-tatangi (13)

11. Te Tūranga o Kupe

I tōna ūnga mai ki Te Whanganui-a-Tara ka ū a Kupe, te kaipōkaiwhenua rongonui, ki te ākau o Maraenui, me tana tapa whakaingoa i taua wāhi - ko "Te Tūranga o Kupe" (te wāhi nui i tū ai a Kupe). Nō muri mai i tana tirotiro haere i te whenua ka whakaaro ia ki te kauhoe atu ki te Aroaro-o-Kupe, tētahi o ngā maramara toka a te taniwha rā a Ngake, i a ia i puta ki Raukawa moana.

12. Te Aroaro-o-Kupe

I a ia e kaukau ana i te taha o te toka rā, ka kawea ia e tētahi ngaru ki runga i ngā koikoi o te toka, ā, ka whara tōna ure. Nā reira te ingoa nei Te Aroaro-o- Kupe, arā, e tohu ana i te wāhi i whara ai tana tinana.

13. Kirikiri-tatangi (Te ākau o Maraenui)

E pā ana tēnei ingoa ki te tangi o ngā kōhatu e nekenekehia ana e ngā ngaru i te tāhuna. I waihotia e Kupe tētahi o ana tāngata ki reira whakatipu kai ai me te whakakī anō i te pātaka kai, i a ia i haere ki te hōpara i te moana o Raukawa. I whakamahia te nuinga o ngā whenua pāraharaha o Maraenui hei māra kai.

Tekau meneti te hikoitanga mai i te pou, ki te pā o Oruaiti.

Whāia te ara ākau mā te tāhuna, tae noa ki Fort Dorset. Hikoia whakarunga te ara, whāia te ranga, tae noa ki runga o te puke, arā ki te pou, mō tētahi tirohanga mīharo rawa atu, ki waho atu o te pā o Oruaiti me te ngutu o te whanga.

14. Te Pā o Oruaiti

Kei runga a Fort Dorset i te pā o Oruaiti, tētahi pā tūwatawata o Rangitāne o neherā. E noho whakaahuru ana ki te puke te pā nei, e titiro ana ki Te Aroaro-o-Kupe. Ko Maraenui te whenua pāraharaha e noho ana i te taha o Oruaiti, e noho hoki ana i raro o Whetū Kairangi. (te wāhi i noho ai ngā tāngata o Kupe ki te whakatipu kai). He māra nui tēnei mā ngā tāngata i noho tata, ā, nā te hao-whenua o te tau 1460, i rahi ake ai te whenua, i kaha pirangitia ai e rātou.

Nā reira, he tata ake te ūnga o Kupe, arā Te Tūranga o Kupe, ki te take o te puke - te wāhi o te ākau i mua i te rū whenua.

Ehara i te mea nō mua anake te wā i whakamahia ai tēnei rohe hei mātaki i ngā ope taua e kuhu mai ana i te whanga, engari i te wā o te pakanga tuarua hoki i whakamahia te wāhi nei nā runga i te pōhēhē kei tau mai te pakanga ki konei.

Ko te tikanga o te ingoa o O-rua-iti, arā, he rua iti i reira mō ngā putunga kūmara me ngā rīwai. Tērā pea nō konei te ingoa e kīia nei ko te rīwai Rua.

Hoki atu ana ki Seatoun mai i te tiriti o Hector ka huri matau ki te tiriti o Dundas, kātahi ka huri mauī ki te tiriti o Inglis. Whāia te tiriti mā te poka tata, ki te tai hauāuru. Haere tonu mā te ākau ki te whanga o Tarakena.

Whakatūria tō waka ki te tūnga waka e tohua ana e te pou, kātahi ka hīkoi atu i te ara poto ki te tohu maumaharatanga mō Ataturk, kei te mutunga o ngā kaupae. Ka taea te kite atu ngā wāhi 15, 16 me 17 mai i konei.

15. Te Pā o Rangitatau.

Ki te titiro ki te ranga o te taha rāwhiti, ka taea te pōhewa i te pā tūwatawata a Rangitatau e tū ana hei ārai mō ngā whakaekenga ope taua, e whakatata mai ana ki Whetū Kairangi mai i te moana, me tōna tirohanga ari ki te moana o Raukawa me ngā wāhi pātata ki te whanga. He nui ngā wā i whakamahia e te kāinga o Poito te pā nei hei toi mō ngā wā o te pēhitanga me ngā wā e kaioraora mai ana te hoariri.

Ko te wai māori i tīkina mai i te wai o Poito, ā, koirā tonu te wai māori mō te pā o Poito. He hī ika, he mahi kaimoana te mahi a te tangata o ēnei kāinga e rua, ā, koinei tonu ā rātou kai nui.

16. Te Pā o Poito

I runga ake o te taha uru o te awa o Poito, te pā o Poito mehemea e tiro whakarunga ana ki te whārua mai i tētahi karahiwi. He pā tuwatawata e tū ana i konei me te maha o ōna upanepane. I hinga ngā pā nei i te ekenga nui o ngā ope taua mai i te raki, i ngā tau 1819-20. He nui ngā tāngata i mate i te wā nei.

17. Rangitatau

He pā anō nō Ngāi Tara i te ranga o te taha rāwhiti e taea te kite atu i tēnei rā tonu. Kei te tōpito o te taha rāwhiti o te karahiwi tētahi awarua, Te āhua nei he tomokanga tawhito mai i te tāhuna o raro. He papanga kāuta kei runga ake i te ranga.

Ahu whakamoana ana, ko ngā toka a Te Kaiwhatawhata, kei te wāhi o Palmer Head, he wāhi pai mō te hī hāpuka.

Haere tonu mā te ākau ki Te Mupunga ka tū ki te pāka o Shorland i te kokonga o ngā tiriti o Reef me Te Esplanade.

E tohu ana tēnei pou i te papanga kāinga o Te Mupunga, ā, whakawhiti atu i te tiriti, ko te motu o Tapu Te Ranga.

18. Te Mupunga Kāinga

He wāhi pai tēnei nō Ngāi Tara rāua ko Ngāti Ira, he nōhanga kāinga i mua i te taenga mai o te Pākehā. I whakamahia ngā puke me ngā pāraharaha o konei hei tūnga pā. Kua kitea i te wāhi nei ngā umu tawhito, ētahi para kōhatu, para anga, para kōiwi, tae noa ki ētahi kōiwi tangata.

Titiro atu ki te moana mai i tēnei wāhi kia kite i te motu, a Tapu Te Ranga.

19. Te motu o Tapu Te Ranga

He motu tēnei i whakamahia i te nuinga o ngā wā hei pā whakamarumaru, ā, i takapapatia te taumata hei wāhi titiro mataara. I waihangatia hoki he taiapa kōhatu hei āwhina ki te ārai i ngā whakaariki. E ai ki ngā kōrero, he wāhi whakaruru tēnei nō Tamairanga, te wahine a Whanake, te ariki nui o Ngāti Ira, me ana tamariki. I te pakanga whakamutunga i panaia atu a Ngāti Ira mai i te Whanganui-a-Tara. I te wā e ekengia ana te motu nei e te hoariri, i rere a Tamairanga me ana tamariki mā runga waka ki te ākau, ki te motu o Mana kimi oranga ai.

20. Te Pā o Uruhau

He pā tūwatawata a Uruhau, nō te huinga pā e tū tū ana ki te ārai ake i te pā nui o Whetū Kairangi mai i ngā ekenga ohorere. Ko te tikanga o tōna ingoa - "he kūrae hauhau" te wāhi nei. E kīia ana, hei tīmatatanga i mua i te whakaekenga o te pā a Whetū Kairangi e Muaūpoko i karapotia e rātou a Uruhau engari nā te muha o te pakanga ka patua rātou.

Hoki atu ki te tiriti, The Esplanade, ka huri taha matau ki te tiriti o The Parade. Taraiwa whakateraki mā te Parade, kātahi ka huri taha mauī ki te tiriti o Tamar, huri matau i te tiriti o Eden, huri mauī i te tiriti o Seine ka huri mauī ki te tiriti o Rhine. E noho whakarunga ana a Tapu Te Ranga, āhua haurua nei te pikinga o te tiriti o Rhine, ki te taha matau.

21. Tapu Te Ranga

He marae hou tēnei, he marae ahurei hoki ki te ao Māori. I tīmataria i te tau 1974. Ko te ngākau remurere o Bruce Stewart tēnei whakatutanga marae, a Tapu Te Ranga, ā, he tangata hanga whare, pupuri hītori anō hoki ia.

Ko te ata o te marae o Tapu Te Ranga e kite pōhewatia e te tini me te mano, ko tētahi ata nui, ā, e iwa rā anō ōna tūāpapa. E ai ki a Bruce, i hanga katoatia mai i ngā para a te katoa. He pouaka pupuri motukā kē ngā pakitara, mai i te rawa ahumahi tawhito o Todd Motors. He ātaahua te whenumi o te tāwhaowhao me ngā taputapu noa ki roto i tēnei whare.

E ai ki a Bruce:

"I kite ahau i ngā rāpihi e porowhiua ana e te tangata, ehara

ana i te rāpihi. He tino ātaahua kē ngā mea i

porowhiua, ā, i nāianei kua oho ake te tangata ki tēnei

āhuatanga. He totara kē ngā papa, arā, kāre e taea

te hoko i nāianei. He rāpihi katoa ngā hanganga nei.

Nāku i kohikohi, kātahi ka waihangatia te whare me ōna papa

e iwa nei mai aua rāpihi."

Heoi, ēhara a Tapu Te Ranga i te hanganga whare papa-iwa anake. He whakahoki ā-wairua i tētahi mea ki a Papatūānuku. Kua tīmataria e Bruce tētahi tūmahi whakatō hanganga hou mātātaki e kapi ana i ngā puke potapotae.

He mea mīharo, ā, ehara i te moumou wā te haere ki te tirotiro i te marae o Tapu Te Ranga engari, me waea atu i te tuatahi nā te mea he nui tonu ngā hui ka tū ki tēnei marae. Ko te nama waea, - (04) 970 6235.

Hoki atu ki te rori ākau ka haere tonu mā te rori o ōwhiro Bay.

I te whakawhitinga o ōwhiro Bay huri ki te taha matau, ki te rori o Happy Valley ka tū i te pāka tākaro i te taha mauī. Kei raro i te tahataha ētahi rua kai, i muri i te Pou. Kei runga i ngā puke o ia taha o te whārua o ōwhiro Kāinga, ā, kei reira hoki ngā tūāpapa o ōwhiro.

22. Ngā Rua Kai

Ko te tikanga o ōwhiro, he "pō kore mārama" ā, i ahu mai i a Whiro, te rā tuatahi o te maramataka.

Ki te titiro whakararo i te pakohu, i muri i te pāka tākaro i te taha o te awa, mārama te kite atu i ngā rua kai o neherā, hei whakarato i ngā kāinga me te pā o ōwhiro Bay.

He whakahirahira te awa e rere tata ana, nā tana whakamahia hei puna wai mō te inu, ā, hei whakamātao i ngā kai kia noho mata ai. E whakatahe ana i ngā kaupekapeka nui o te awa i ngā aupaki i te taha rāwhiti o te ranga o Te Kopahou me te taha hauāuru o te ranga o Tawatawa.

Ngā Tūāpapa o ōwhiro

Ka kitea atu ngā tūāpapa kua tipua e te pātītī i runga i te ranga e aro ana ki te paeroa. He kāinga tawhito tēnei nō Ngāti Ira. I panaia rātou, ā, ka nōhia e Ngāti Awa i tērā rautau.

Te Kāinga o ōwhiro

He kāinga i te taha rāwhiti o te rori o te whanga o ōwhiro Bay. E kitea ana ngā ahu otaota tata ki te karahiwi i nōhia rā e wai ake. I whakaarohia i nōhia pea e Ngāti Awa, ā, tērā pea he kāinga tō rātou, tata ake ki te wahapū o te awa.

Ki te hoki atu ki te tāone, me haere tonu mā te rori o Happy Valley ki Brooklyn. Mai i konei whaiā te rori matua ki te tāone mā te tiriti o Willis.

Kaituhi: Matene Love.