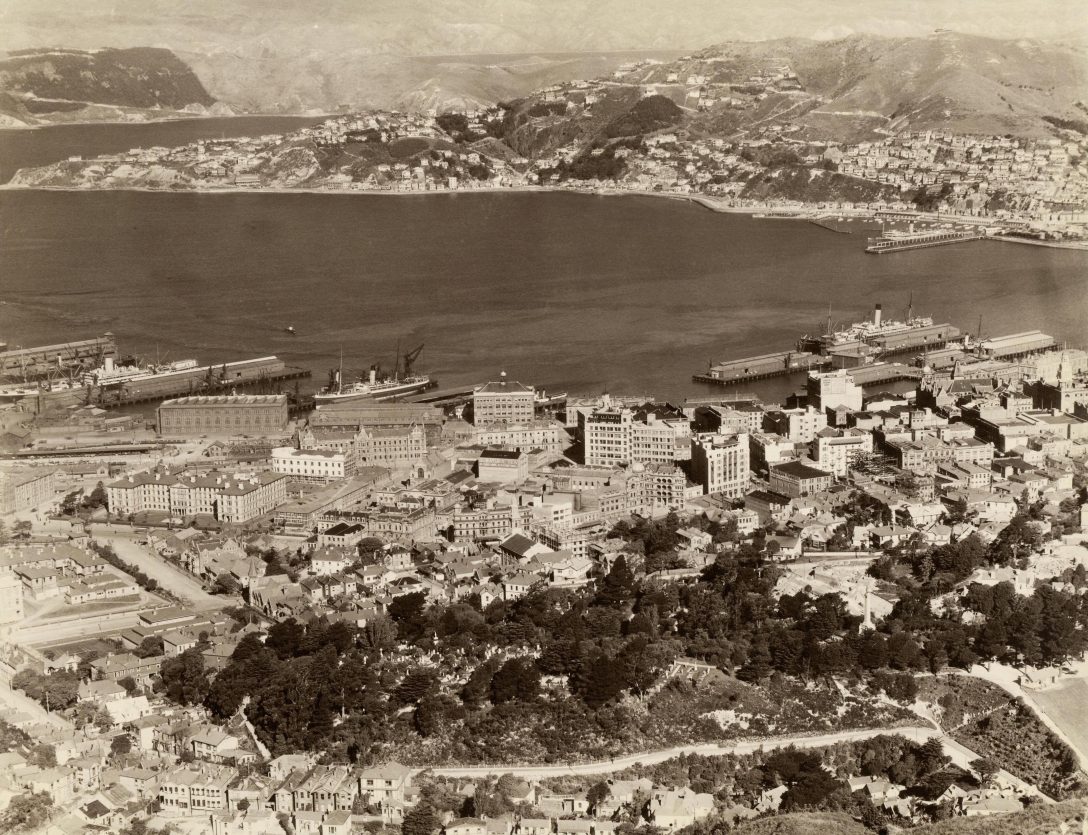

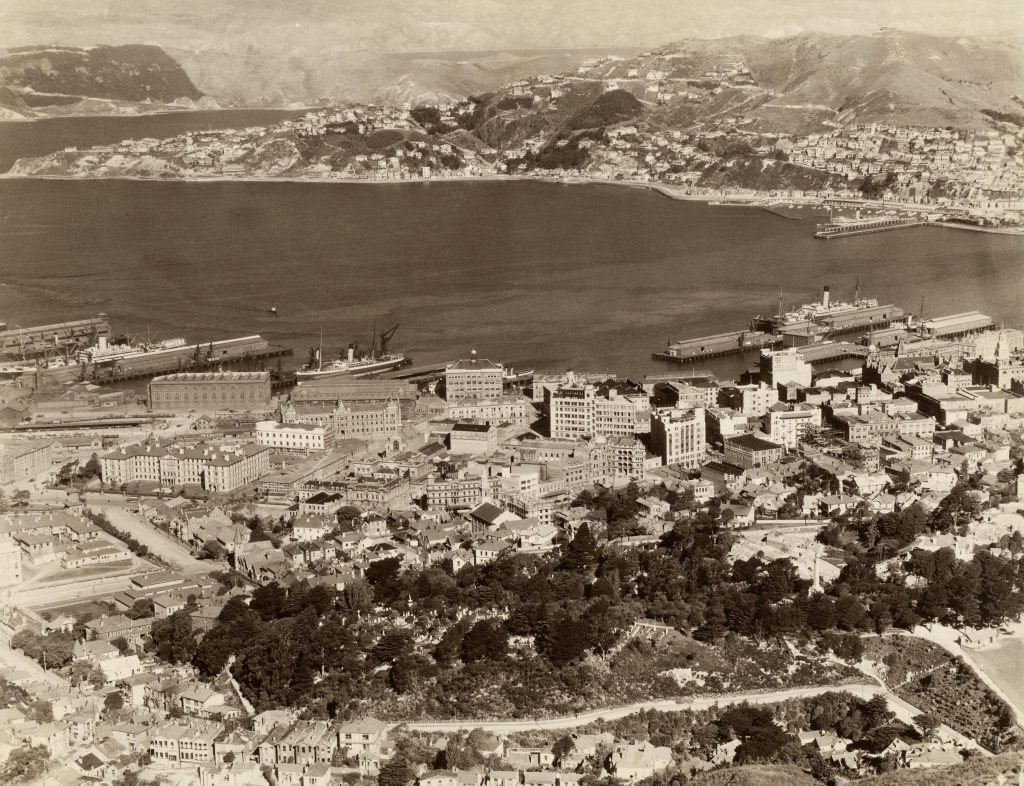

A remarkable photograph captures our city basking in the sun on a calm summer’s day nearly a century ago.

This photo appeared in 1928 in one of the first significant local history books to be published, Early Wellington by Louis Ward. Photographed from the slopes of Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) the image was credited to the Government Publicity Office, an early marketing department that operated as a branch of Internal Affairs to promote New Zealand to tourists and potential migrants. Ward included it as one of the last illustrations in his hefty 500+ page volume to show what the city looked like ‘today’ for his then-readers and the extent of reclamation that had occurred to that point. Much of his original research material was deposited with the Central Library after he completed his work so it’s possible that this is the actual photo which was reproduced in the book. However, photo-lithographic techniques were still quite basic in the 1920s and printers weren’t yet able to reproduce the fine details of photographs and illustrations on a commercial scale so it appears as a somewhat unremarkable picture at the end of the book. On the other hand, the original print is crisp, clear and incredibly detailed indicating that it could be a contact print taken from a glass-plate negative. The large size of plate negatives coupled with their very slow film speed and the fine grain of vintage photographic paper meant that incredible detail can be captured. However, it is often only when images like this are digitally scanned that one can truly appreciate the level of historic visual information they contain.

What makes the photo so striking is just how developed Wellington appears to be in a photograph taken some 96 years ago. The 1920s were a period of tremendous economic growth as the country shrugged off the privations of World War I and moved into the ‘Jazz Age’. Wellington’s population grew rapidly as migrants from the UK continued to arrive in increasing numbers while rural labourers shifted to the city seeking new work opportunities. Technology made huge advances over this period; regular radio broadcasts began and radio and gramophone shops were soon dotted across the inner-city. Horses & carts which were commonplace on the city’s streets in 1920 were starting to become a rarity by 1925. The electricity network was revolutionised when Wellington abandoned the old 110 volt system it had been using since the late 1880s and adopted its current 230 volt AC system. Previously used mostly only for lighting, electric power was now a serious alternative to steam driven machinery in factories and a viable replacement for coal to heat homes, offices and for providing hot water.

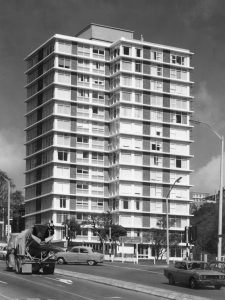

Though the photograph is dated 1928 in Ward’s book, it was almost certainly taken four years earlier with visual clues present in the form of two construction sites. The first is Braemar, a distinctive building next to St Andrew’s on The Terrace which appears in the photo surrounded with scaffolding as it nears completion. Begun in 1924 as a property development on former Presbyterian church land, it opened in early 1925 as one of the first examples of an inner-city apartment building in Wellington.

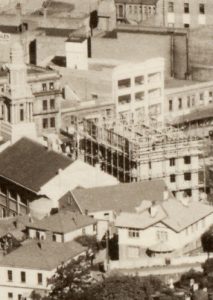

The second is the Druids’ Chambers where the steel girders which make up the internal frame of the building can be seen being assembled on the corner of Woodward Street and Lambton Quay. Work on this began in 1924 and it opened as an office building for the financial and benevolent services branch of the masonic Order of Druids in June 1925. Remarkably, both of these buildings survive to this day. Another pair of buildings shown in the image which are still standing are the Old Government Buildings (the birthplace of the ‘modern’ civil service in NZ and once the largest wooden building in the world) and Shed 21 which appears above it. The exterior appearance of these is largely unchanged but between them lies Waterloo Quay where railyards can be seen extending further south than they do today while the blurred shapes of motor vehicles can be seen moving on the road. However, the lack of traffic or pedestrians on other roads indicates that the photo was probably taken in the mid-late afternoon during a weekend or possibly during the summer holiday period.

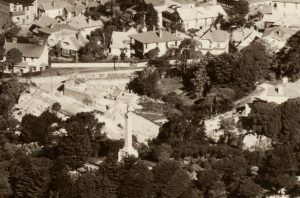

In the centre-right foreground south of the Bolton Street Cemetery, a new residential subdivision is being formed. This is the Easdale St / Kinross St area which was developed from land once owned by the infamous former Chief Justice James Prendergast who had died in 1921. After basic roads had been installed, sections were sold off to members of a new generation of middle-class professionals who employed some of the country’s best architects to design their dream homes. Meanwhile in the lower-left corner, Bowen Street ends abruptly just past the Congregational Church on the corner of The Terrace which is today the site of the Reserve Bank.

In the centre-right foreground south of the Bolton Street Cemetery, a new residential subdivision is being formed. This is the Easdale St / Kinross St area which was developed from land once owned by the infamous former Chief Justice James Prendergast who had died in 1921. After basic roads had been installed, sections were sold off to members of a new generation of middle-class professionals who employed some of the country’s best architects to design their dream homes. Meanwhile in the lower-left corner, Bowen Street ends abruptly just past the Congregational Church on the corner of The Terrace which is today the site of the Reserve Bank.

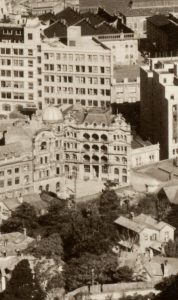

One central building that really stands out in the photo because of its deep-set verandas is the Hotel Arcadia. Located on the corner of Lambton Quay and Stout Street opposite the Public Trust Building, it opened in late 1905 having been constructed to an ornate design that wouldn’t have looked out of place in central Paris. It promoted itself as being Wellington’s finest hotel and featured plush dining and function rooms which were regularly used for balls, formal dinners and receptions for visiting dignitaries. Despite its grandeur, the hotel barely lasted 30 years after it was purchased by the Department of Internal Affairs in late 1938 and demolished the following year to clear the site for the construction of the State Fire Insurance Building, one of the first early-modernist buildings to be constructed in Wellington. This photo and many more like it can be seen on our Recollect site here.

One central building that really stands out in the photo because of its deep-set verandas is the Hotel Arcadia. Located on the corner of Lambton Quay and Stout Street opposite the Public Trust Building, it opened in late 1905 having been constructed to an ornate design that wouldn’t have looked out of place in central Paris. It promoted itself as being Wellington’s finest hotel and featured plush dining and function rooms which were regularly used for balls, formal dinners and receptions for visiting dignitaries. Despite its grandeur, the hotel barely lasted 30 years after it was purchased by the Department of Internal Affairs in late 1938 and demolished the following year to clear the site for the construction of the State Fire Insurance Building, one of the first early-modernist buildings to be constructed in Wellington. This photo and many more like it can be seen on our Recollect site here.