Saturday 11 November 2023 sees the finale of Orchestra Wellington’s ‘Inner Visions’ season with a concert performance of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck. This will be the first performance of Berg’s complete work in New Zealand, nearly a full century after its premiere in Berlin in December 1925. Orchestra Wellington and Music Director Marc Taddei will be joined by a constellation of outstanding singers in the principal roles, as well as the Scholar Cantorum of St Mark’s School, and the Tudor Consort.

This blog will explore some of the background to Wozzeck and highlight some of the books and audiovisual materials in the Wellington City Library that will offer still more context for and analysis of Berg’s opera. Whether you are interested in the history of Wozzeck, Berg’s creative process and the structure of the work, atonality, Expressionism, or the early-nineteenth century play Woyzeck that provided Berg with his source and inspiration, there will be something here for you: Roger Parker, Carolyn Abbate, Theodore Adorno, and several other authors have all written perceptively and revealingly about Wozzeck.

Nearly a century after its premiere, Wozzeck still exemplifies modernism: fifteen dramatic, often anguish-drenched, scenes are made excruciatingly vivid through the astonishing music of Berg that exemplifies the season’s theme of ‘Inner Vision’. The themes of Wozzeck — poverty, jealousy, class difference, the threat of war, paranoia, the brutality of army life, loneliness, careless moralizing, obsession, lust, heavy symbolism, and fragmented relationships — provided ideal material for a German Expressionist opera, especially in the volatile political and social atmosphere of 1920s Germany. However, the story itself is much older. Karl Georg Büchner (1813–1837) — poet, playwright, revolutionary, and latterly, lecturer in anatomy — wrote most of his play Woyzeck in 1836 but, when he died from typhus in 1837, it was unfinished and Karl-Emil Franzos had to piece the sketches and fragments of Büchner’s work together. This task was made more complicated by Büchner’s microscopic handwriting, and the faded ink of the sources. These two factors also contributed to Franzos mistranscribing ‘Woyzeck’ as ‘Wozzeck’. Franzos was able to publish the play in the 1870s, but its first performance at Munich’s Residenztheater only took place in November 1913. Alban Berg would see the play in Vienna in 1914, a few months before the outbreak of World War I, and soon began contemplating an operatic treatment of the drama. Little did he know that by the time he completed the piece several years later, it would be in Europe cut into pieces following years of brutal mechanized conflict.

Years before, Büchner had based Woyzeck on a true story, a grim saga involving a man called Johann Christian Woyzeck who grew up in poverty and scratched a living as a barber, bookbinder, servant, soldier, and tailor. He lived with a widow, Christiane Woost, whom he stabbed to death in a fit of rage. The subsequent murder case took several years to decide, as doctors tried to determine whether Woyzeck was criminally responsible for stabbing Woost, or insane. Eventually, he was determined to know the difference between right and wrong, found guilty, and sentenced to death; Woyzeck’s execution by public beheading took place in Leipzig in August 1824.

Although Büchner was a child at the time of the murder and trial, the Woyzeck case was a sensational one and well-documented, which perhaps drew his attention to the case as an adult and medical doctor. In Büchner’s play, and subsequently Berg’s opera, the soldier Wozzeck is subjected to medical experimentation; just as the Leipzig murderer was assessed for several years by doctors to determine his mental state, Büchner’s titular hero earns extra income by participating in medical tests, resulting in the Doctor telling him he must live entirely on peas to maintain his sanity and health. Meanwhile, Wozzeck is instructed by his Captain to take life calmly as he has many years ahead of him; in his next breath the captain says Wozzeck’s a decent man but without moral sense, citing the existence of Wozzeck and Marie’s illegitimate son. With great dignity, Wozzeck replies that despite the moral posturing of his social betters on earth, the Lord would not spurn his son just because ‘the Amen was not spoken before the mite was made.’ In a moment that foreshadows Brecht and Weil’s Threepenny Opera, Wozzeck reminds his Captain that conventional morality is a luxury that he cannot afford:

Wretches like us! You see, Herr Hauptmann, wealth, wealth! Without money! Let one of us try to bring his own kind into the world in a fine moral way! We have flesh and blood, too! Oh, if I were well-bred, and had a top hat, a pocket watch and a monocle and a proper accent… then I would be virtuous, too! It must be wonderful to be virtuous, Herr Hauptmann. But I’m only a poor man! Men like us always will be ill-fated in this world and in any other world! I think, if we ever got to Heaven, we’d all have to manufacture thunder!”

Berg’s decision to use Büchner’s play as a source for his opera was a very personal one, influenced partially by his own observations. After growing up in a well-off middle-class family and living a comfortable adult life in intellectual and artistic circles, Berg then experienced something of the life of the lowly soldier during his time in the Austrian army. Although upon entering the army in August 1915, a year into World War I, he discovered how to join an ‘artists’ company’ that turned out to be full of people he knew, the conditions in which private soldiers were expected to live were dehumanizing.

Berg was given a uniform that was too small and extremely smelly. At an early training camp, he and his fellow soldiers had to stand in pouring rain outside their train, before being crammed inside, soaking wet, for a seven-hour journey, before a dinner of black coffee and a cold night in a rock-hard bed. He wrote that at the camp on the Hungarian border, ‘the lavatories are revolting, but, as I said, these are external things which one can easily get over.’ However, as Berg soon learned, the daily grind of training, poor food, and excessive drilling and route marches could soon break both the spirit and the body of the private soldier. The officers, meanwhile, lived a far more cushioned life. These experiences would later emerge in Wozzeck: in Berg’s libretto, he substituted beans for Büchner’s peas and used an Austrian vernacular term for mutton (Schoepsenfleisch) instead of Büchner’s doctor’s ‘Hammelfleisch’ as these were part of his army rations (‘we are given mutton, which is prepared in the most disgusting manner.’)

These and other degradations were part of the private soldier’s preparation for war. This theme is clear in the opera, as Marc Caplan has written, articulating ‘a sense that life is a farce for the ordering classes (the Captain, the Doctor) and a tragedy — to the extent of melodrama — for the ordered classes (Wozzeck, Marie, the miscellaneous vagrants in the tavern).’ To discover more about these themes, or engaged with analysis of Berg’s music, and how his opera was received, the following titles will take you further:

The birth of an opera : fifteen masterpieces from Poppea to Wozzeck / Rose, Michael

Michael Rose slices through centuries of myth-making and romanticising to document the creation of fifteen operas, from Monteverdi’s Poppea (first performed in 1643) to Berg’s Wozzeck (1925). Rose examines the manifold complexities of making operas, which in the case of Wozzeck were unique. Using primary sources, such as Berg’s correspondence, Rose examines how and why Berg decided to use Büchner’s sketches and fragments as a source for his opera, then the difficulties of turning these into a useable libretto that made dramatic and musical sense while not diluting Büchner’s text. Rose also explains very clearly the structure of Wozzeck’s three acts and fifteen scenes. Equally important in Rose’s account of Wozzeck‘s creation are the details of how the score was printed, the process of rehearsing and staging the opera for the first time, and its immediate reception. The extracts from Berg’s letters about this time are deeply engaging, drawing us into the events of nearly a century ago with all the excitement and anxiety attendant on premiering a daring new piece.

Berg’s Wozzeck : harmonic language and dramatic design / Schmalfeldt, Janet

Berg’s Wozzeck : harmonic language and dramatic design / Schmalfeldt, Janet

Schmalfeldt’s 1983 analytical of Wozzeck is a meticulously detailed study of the opera through the lens of Pitch-Class Set Theory, and her book may appeal more to those with a serious interest in the analysis of atonal music. Schmalfeldt was inspired to undertake her project by the sheer daring of Wozzeck. As Schmalfeldt writes in her preface: ‘At a time when atonal composition was still largely confined to the production of short works and miniatures, Alban Berg’s decision to compose a full-length atonal opera on the … fragmentary and disturbingly revolutionary Woyzeck showed great courage. The outcome of that decision — Wozzeck — stands today as one of the greatest works in the history of opera, one whose brilliant orchestration alone can ravish even those listeners who are otherwise not fond of twentieth-century music and makes an impact never to be forgotten.’ Schmalfeldt’s work is complex and highly technical, exploring how Berg’s pitch structures are integral to his characterization of Wozzeck, Marie, and others. She also demonstrates how these pitch structures provide coherence throughout the opera, in a masterly theoretical exegesis.

Alban Berg / Monson, Karen

Alban Berg / Monson, Karen

Described as a ‘vivid portrait’ of the composer and the world he lived in, Monson’s biography of Berg also addresses selected musical works in detail. Monson charts Berg’s reverence for Schoenberg, as well as the frictions between them; she writes about Berg’s marriage to Helene Nahowski, and his extramarital relationship with Hanna Fuchs-Robettin; Berg’s thoughts on the future of music and opera, and his own identity as a self-described Austrian composer, are also central to Monson’s work. Two chapters, ‘Discovering Wozzeck‘ and ‘The Success of Wozzeck’ deal in detail with the creation and performance of Berg’s opera, and Monson highlights Berg’s sense of affinity with the opera’s protagonist, especially after experiencing (albeit for a relatively short time) how army life dehumanized soldiers. Revealingly, Monson also documents how the premiere of Wozzeck in 1925, and the largely positive reception the opera inspired concerned the composer: shaped by his years of Schoenberg discipleship, he worried that public approval meant his work was facile and weak, a fear he was happily able to overcome.

The operas of Alban Berg: Wozzeck / Perle, George

Perle’s study of Wozzeck is again a technical and analytical exploration of Berg’s opera, but also engages more with contextual matters that illustrate links between Wozzeck, Berg’s training and earlier music, and demonstrates the originality of Berg’s musical thinking. Perle also considers Berg’s approach to representation and symbols in the music of Wozzeck, explicating the role of Leitmotiv, and how Berg’s use of this technique corresponds with, and steps away from Richard Wagner’s Leitmotiv ‘system’. Again, as Perle demonstrates in relation to Berg’s use of musical form, his approach to Leitmotiv is entirely original. For the newcomer to Wozzeck, the sixth chapter and first appendix are invaluable guides to the genesis of Wozzeck and the external forces that governed Berg’s creative process; Appendix I presents Berg’s own guide to the ‘Preparation and Staging of Wozzeck‘, giving the reader fascinating access to the composer’s vision for the piece.

Alban Berg, master of the smallest link / Adorno, Theodor W.

Theodor Adorno (1903-1969), philosopher, critic, and aesthetician, met Alban Berg in 1924 at the Frankfurt premiere of ‘Three Fragments from Wozzeck‘. A few months later, in February 1925, Adorno travelled to Vienna to study with Berg and immersed himself in the musical and cultural life of the Austrian capital. Berg became a mentor and friend, and in Alban Berg, master of the smallest link, Adorno offers us a unique perspective on Berg, drawing on his experiences as a student and their friendship. Alongside his analysis of Berg’s music and intellect, Adorno’s appreciation of Berg’s personality is revealing, noting his capacity for friendship, his ‘boundless goodness’ as well as the paradox between his reliance on Arnold Schoenberg for musical validation and his originality and determination; for example, the composition of a full-length atonal opera. Wozzeck is an example of this, an opera that Adorno believes nobody, but Berg could have composed, ‘In order to understand the relationship between Berg’s meticulously crafted opera and Buechner’s intentionally [sic] sketch-like fragments, to grasp what brought the two together in terms of aesthetic economy, it may be well to remember than one hundred years lie between the drama and the composition. What Berg composed is simply what matured in Büchner during the intervening decades of obscurity.’

A History of Opera : the Last Four Hundred Years / Abbate, Carolyn and Roger Parker

Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker are preeminent among opera scholars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, their work encompassing an immense breadth and depth of knowledge, coupled with an inimitable gift for communicating complex interpretive ideas. A History of Opera: The Last Four Hundred Years is an authoritative volume weaving together the history, materials, and literature of the operas they discuss, with commentary on how these musical/theatrical works survive today, very often in conditions extremely foreign to those in which they were created. In Chapter 18, starkly titled ‘Modern’, Abbate and Parker address Wozzeck in the context of other early twentieth-century works, showing that this work of extraordinary originality does not exist in a modernist vacuum, but drew on much that had come before, including Richard Strauss’s earlier operas. Parker and Abbate describe Wozzeck as an opera that is ‘hyper-structured’ but ‘wears its learning lightly’: Berg always wanting to draw his audience into the vivid human drama of the opera, rather than using atonality and abstraction to exclude the uninitiated.

The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera

The Cambridge Companions series is an invaluable resource for erudite and well-written essays on many musical topics that appeal to experts, interested newcomers, and everybody in between. The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera is no exception: in addition to a useful chronology at the start of the book (which may surprise some readers with the sheer number of operas created in the twentieth century), the essays on ‘Expression and Construction’ in the operas of Berg and Schoenberg (Alan Street) and Austria and Germany between 1918 and 1960 are especially relevant to Wozzeck. Caroline Harvey’s ‘Words and Action’ chapter also explores how twentieth-century innovations, most obviously psychoanalysis, had a transformative effect on composers and librettists, including Alban Berg. Arnold Whittal’s opening chapter, ‘Opera in Transition’ addresses the social and political changes in the early part of the twentieth century that affected the art form, as well as how nineteenth-century ideas about repertory and canon continue to influence how we listen to and think about opera.

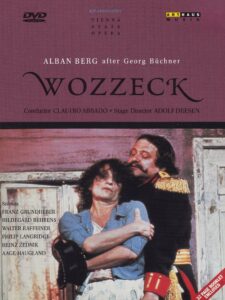

Wozzeck / Berg, Alban

Wozzeck / Berg, Alban

This 1987 recording with the Vienna State Opera and Philharmonic, conducted by Claudio Abbado, has been agreed by a variety of critics to be one of the finest, perhaps even the definitive, recordings of Wozzeck. The cast is certainly outstanding. Abbado, they say, strikes an ideal balance between the twin forces of Berg’s music, the lyrical revenants of late-nineteenth-century Romanticism alongside the Expressionist extremity. Franz Grundheber (Wozzeck) and Hildegard Behrens (Marie) inhabit these challenging roles with apparent ease, their Sprechstimme sounding so natural that one might imagine that they always communicated this way. The Doctor and Captain likewise embody their characters with great intelligence. One criticism of this recording is that the balance is weighted towards the orchestra, which occasionally means that the texture is dominated by an unexpected instrument; at the same time, though, the spontaneous elements of this recorded performance provide many unique moments that more than compensate.