In late 1937, an exciting news announcement quickly spread across Wellington; the RMS Empress of Britain was going to visit the city the following year. Launched in 1930, she was one of the largest, fastest and most luxurious ocean liners of the period.

Only slightly smaller than the Titanic, her design incorporated lessons learnt from the tragic sinking of that ship and included double-steel plating to deal with the ice-infested waters which were common on her main Atlantic run between England and Canada. As trans-Atlantic passenger numbers would fall dramatically each winter and the freezing of the St Lawrence River made Canadian port access difficult, towards the end of each year she would be seasonally converted into a luxury cruise liner and it was in this capacity that she visited New Zealand.

She first visited Sydney and Melbourne where hundreds of thousands of spectators turned out to see the ship. Then on 6th April 1938 she crossed the Tasman Sea, heading first for Milford Sound which had been promoted to passengers as the highlight of the cruise, before coming to Wellington. As the vessel approached NZ, much was made of her size and technology. Readers of newspapers were advised of how passengers could make a ship-to-shore phone call to London if they wished…at a cost of £3/12 for a three-minute conversation, the equivalent today of around NZ $400! Features included a regulation size tennis court, picture theatres and a ‘country fair’ with a coconut shy, hoopla stalls and a fortune teller. There were 390 staff employed in the catering department alone, while the ship’s three great white funnels could be used as a beacon in emergencies; when illuminated by powerful flood lamps they could be seen by other vessels 50km away. When she arrived in Wellington on the morning of Sunday 10th April 1938 (thankfully a calm sunny day) excitement was at a fever-pitch. A live radio commentary from Mt Victoria commenced on Radio 2YA as soon as she was spotted off the Wellington heads and thousands of people lined the shore and hillsides to catch a glimpse of what was then the largest passenger vessel ever to enter the harbour. That afternoon there was a radio broadcast of a live concert given by the ship’s orchestra, while what was said to be “the wealthiest and most distinguished aggregation of passengers ever to visit Wellington” toured the city. Car-owning locals picked up random passengers from Pipitea Wharf, inviting them to their homes and driving them all over the region to show them the sights. When she departed that evening just after 11pm, songs were sung, thousands of streamers were thrown from the deck by passengers and Oriental Bay was jammed with cars lined up nose-to-bumper with all of them sounding their horns to echo the horn blasts coming from the ship.

After being converted into a troop carrier for World War II, she made another brief visit to Wellington in May 1940 to transport New Zealand soldiers to the UK. Unlike her visit two years earlier, wartime restrictions meant that this time there was no public announcement, no media coverage and not even a simple listing in the Evening Post’s daily ‘shipping news’ column. With all of the secretive war-related shipping activity that was happening in the harbour at the time, many in the city may have been unaware that the great ship had returned. However, five months later came some shocking news that was reported and which likely would have had some people in the city in tears; on 26th October 1940 the Empress of Britain was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland by a German U-Boat. She was the largest passenger vessel lost during the war and the largest vessel of any kind to be sunk by a U-Boat.

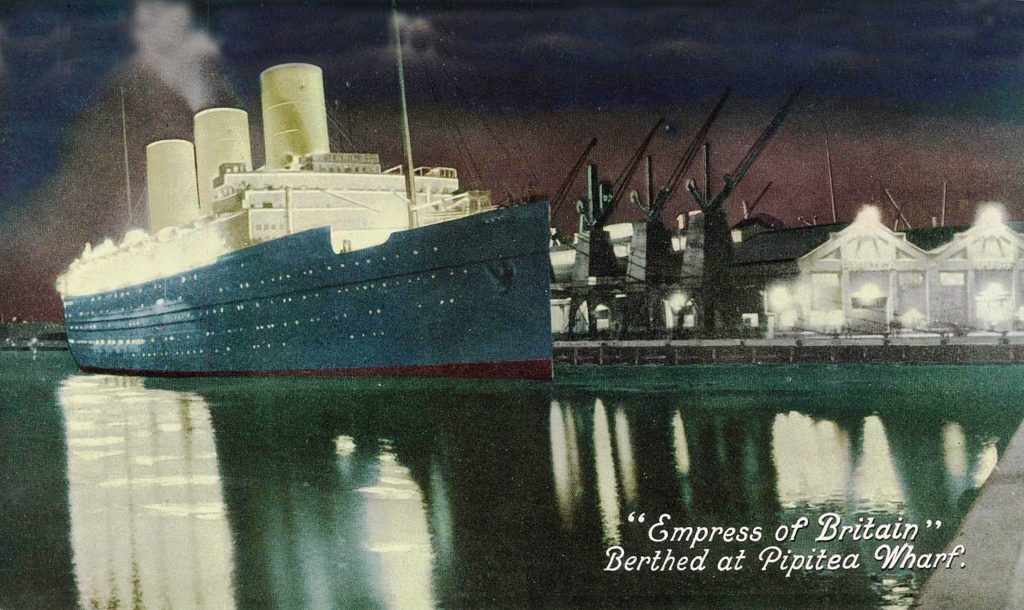

The hand-tinted photo above captures the ship tied up at Pipitea Wharf on the evening of 10th April 1938 shortly before its departure to Auckland (by coincidence, this was 30 years to the day before the storm that resulted in the sinking of the TSS Wahine). Pipitea wharf no longer exists after it was demolished for the construction of the container wharf in the late 1960s but it was located just north of the Wellington Railway Station. You can see the photo in full detail and read more about the port’s activities during this period in this Handbook of the Wellington Harbour Board which has been digitised on our Recollect site.