Strike the viol, touch the lute,

Wake the harp, inspire the flute.

Sing your patroness’s praise,

In cheerful and harmonious lays.

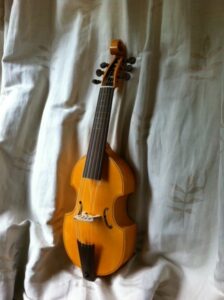

The viol — a bowed, fretted string instrument also known as a viola da gamba — rose to prominence in Europe at the end of the fifteenth century, and by the seventeenth century, it was one of the most popular ensemble and solo instruments. In Renaissance England, the viol consort, a group of viols of different sizes (treble, tenor, and bass), was one of the preeminent ensembles of the day, playing extraordinarily complex music; right through to the mid-eighteenth century, the viol remained an important solo instrument, especially for French and German composers. Eclipsed by the violoncello in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the viol was relegated to the status of a quaint relic until the ‘early music revival’ of the twentieth century reignited interest in viols and their music. Today, different members of the viol family can be found in many ensembles — and not only those specialising in early music or historical performance. The sound of viols and the virtuosity of their players inspire increasing numbers of contemporary composers (Nico Muhly, Sally Beamish, James MacMillan, and New Zealand’s own Yvette Audain, and Ross Harris to name a few) to write music for solo and ensemble viols.

Locally, Wellington is home to Aotearoa’s only viol consort, the Palliser Viols. While the repertoire of the group is predominantly that of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they also demonstrate the versatility of the viol by commissioning and performing new works including Ross Harris’s Gaudete and Image of Melancholy, Dame Gillian Karawe Whitehead’s Douglas Lilburn, travelling on the Limited, regards the mountains in the moonlight and Colin Decio’s Lord have Mercy. And, perhaps more unexpectedly, there is a specialist maker of viols based in Wellington as well: Alan Clayton’s beautiful instruments — which he makes on commission from musicians here and overseas — can sometimes be seen at Alastair’s Music in Cuba Street. Today’s blog explores some of the recordings of music played by viols in different combinations and emerging from different countries and eras.

Lachrimae or seven tears / Dowland, John

The viol consort — typically a group of three to six viols of different sizes (treble, tenor, and bass) — was one of the preeminent instrumental ensembles in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. In addition to playing extremely complex and sophisticated music by renowned composers of the era including Orlando Gibbons, William Byrd, William Lawes, Anthony Holborne, John Jenkins, and Henry Purcell, viol consorts also accompanied secular and sacred vocal music. In this recording by the consort Phantasm and lutenist Elizabeth Kenny we hear a magnificent set of melancholy consot pieces, John Dowland’s Lachrimæ or seaven teares figured in seaven passionate pavans, with divers other pavans, galliards and allemands, set forth for the lute, viols, or violons, in five parts (1604). The set opens with the seven pavans built around a descending four-note motif (A-G-F-E) that suggests falling tears. A seventeenth-century connoisseur would have recognised these notes as the same ones that opened Dowland’s song ‘Flow my teares’ in his Second Book of Songs in 1600. Phantasm navigates the intricate labyrinths of Dowland’s melancholy with skill and lustrous resonance.

The Royal consort / Lawes, William

The Salisbury-born composer William Lawes (1602-1645) became part of the musical retinue of the Prince of Wales, later King Charles I, in the mid-1620s. His works include sacred and secular vocal music, theatre music, music for harp and lute, and music for viols. Lawes enlisted in the army at the time of the English Civil War, continuing to serve the monarch as a soldier as well as a musician. Perhaps because of Lawes’ talent, attempts were made to shield him from the dangers of battle, but in 1645, Lawes took part in the Siege of Chester, and was killed. The loss of this remarkable talent in the service of the monarch occasioned many tributes from other composers and Royalist poets alike. Lawes’s Royal Consort, likely dating from the late 1620s, is a collection of ten sets of dances that demonstrate Lawes’s ingenuity as a contrapuntalist as well as his command of dance idioms. The musicians of Phantasm — joined by guests Daniel Hyde (organ), Elizabeth Kenny (theorbo), and Emily Ashton (viol) — draw out the wit and sensuousness of Lawes’s music with agility and intuition. In addition to the superb playing, this recording is enhanced by the informative CD booklet: Laurence Dreyfus, who founded Phantasm in 1994, is an eminent musicologist with eclectic research interests, and writes a characteristically provocative essay about the Royal Consort, Lawes, and historical performances mythologies to set the music in its cultural context.

Songs & airs / Purcell, Henry

A collection of Purcell’s eloquent songs, performed by an ensemble of distinguished musicians of the twentieth century’s British early music revival. Soprano Emma Kirkby demonstrates her supreme command of Purcell’s idiom, ably supported by Catherine Mackintosh (violin) and a continuo group of big names, including Anthony Rooley (lute), Christopher Hogwood (organ and spinet), and Richard Campbell (viol). Each song and air exemplifies Purcell’s sublime aptitude for heightening the expression of the texts with his harmony, using the devices of classical rhetoric translated into music. Two particular highlights of this recording are ‘If music be the food of love’ and the poignant ‘Bess of Bedlam’ and ‘If music be the food of love’. The versatility of the viol as a continuo instrument comes to the fore in accompanying Emma Kirkby: resonant, visceral, and sprightly by turns, Richard Campbell’s viol heightens the expression of the vocal line, emphasizing that Purcell’s songs and airs are true ensemble works.

L’Apotheose de Lully / Couperin, François

L’Apotheose de Lully / Couperin, François

In 1724 and 1725, François Couperin (1668—1733) published two grand trio sonatas, both examples of his ambition to realise the réunion des goûts, a reconciliation between the French and Italian styles of composition that would achieve new heights of aesthetic perfection. L’Apothéose de Corelli (1724) is a seven-movement programmatic work, in which the movements depict the Italian composer Arcangelo Corelli’s arrival in Parnassus, where he sips from the Hippocrene spring (a source of inspiration) and meets Apollo himself. Although the music is unmistakably by Couperin, he demonstrates his understanding of Corelli’s brilliant sonata style, with its languorous slow sections and sparkling contrapuntal writing. L’Apothéose de Lully (1725) is a longer work, which opens with Lully in Elysium, playing in concert with the Shades; Mercury arrives to herald the approach of Apollo and gives Lully a violin, and a place in Parnassus. When Lully’s ascent is complete, he is greeted warily by Corelli and the Italian muses. Apollo then attempts to persuade the two composers to adopt a réunion des goûts, and the two composers play airs to each other, leading to ‘La Paix du Parnasse’ in which the French muses accept Italian music as long as its titles are given in French. In this music, the viol switches between playing the basso continuo line, and a lithe independent role.

The complete flute sonatas / Leclair, Jean-Marie

The complete flute sonatas / Leclair, Jean-Marie

The flute sonatas of the French composer Jean-Marie Leclair (1697-1764) can be found in his Op. 1 Premier livre de sonates (1723), his Op. 2 Second livre de sonates (1728), and the Op. 9 Quatrième livre de sonates (1743). Primarily composed as sonatas for violin and basso continuo, two sonatas from Op. 1, five from Op. 2, and two from Op. 9, are also suitable for the flute. In each work, the characteristics of the goûts réunis — in which elements of the Italian and French styles of instrumental composition are synthesized — are clear, a testament to Leclair’s innate and creative grasp of both styles following his years in Italy. The structure of Leclair’s sonatas is predominately Italianate, modeled on Corelli’s sonatas, while other stylistic elements draw on the music of earlier French masters of the viol and keyboard, including François Couperin, Jean de Sainte-Colombe, and Marin Marais. In this recording, three masters of historically-informed performance, Barthold and Wieland Kuijken, and Robert Kohnen, offer eloquent readings of Leclair’s sonatas; Wieland Kuijken’s intuitive approach to playing basslines on the viol lends an eloquent support to the flute.

The Celtic viol : airs and dances / Savall, Jordi

The Celtic viol : airs and dances / Savall, Jordi

The Celtic viol II : treble viol & lyra viol / Savall, Jordi

Of all the musicians who contributed to the revival of the viol family in the twentieth century, few have done more than Jordi Savall. The Spanish viol player and conductor has helped to reignite interest in medieval, renaissance, and baroque music through his imaginative, dramatic, and virtuosic performances and recordings of repertoire from France, the Iberian peninsula, England, Germany, and beyond with his ensembles he founded: Hespèrion XXI, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, and Le Concert des Nations. Savall and Andrew Lawrence-King’s 2009 album The Celtic Viol: Airs and Dances is a vibrant collection of Scottish and Irish music, performed on treble viols and a sixteenth-century fiddle. Harpist Andrew Lawrence-King, playing the Queen Mary Harp and Irish Psalterium, is far more than an accompanist here, providing rich and atmospheric support for Savall.

Pièces à deux violes du premier livre / Marais, Marin

Pièces à deux violes du premier livre / Marais, Marin

The pieces de violes of Marin Marais were acknowledged during his lifetime to be the very summit of viol music. In 1732, the German theorist Johann Gottfried Walther wrote of Marais that he was the ‘incomparable Parisian violist whose works are known all over Europe’, and his artistry was unprecedented and unsurpassed, except perhaps by that of his teacher, Monsieur de Sainte-Colombe. Marais spent almost his entire life in service to the church or the monarch: he sang in the choir at St Germain-l’Auxerrois as a child, then studied with Sainte-Colombe and Lully, before becoming a member of Louis XIV’s musical establishment in 1676. Subsequently, Marais was appointed Ordinaire de la chambre du Roi pour la viole in 1679. There survive nearly 600 works for viols by Marais, most of which were published in a series of five livres between 1686 and 1725. The first livre, dating from 1686, contains suites of dances that epitomize the refined and dramatic virtuosity of Marais’ music.

The complete fantazias / Purcell, Henry

Fretwork is now a venerable ensemble, founded thirty-seven years ago. While there have been personnel changes over the decades, Fretwork remains synonymous with remarkable performances of a wide range of repertoire, from Cornyshe, Weelkes, and Lupo to George Benjamin and Michael Nyman. In 2008 they recorded Henry Purcell’s complete fantazias. These fantazias are a testament to Purcell’s contrapuntal ingenuity, as he expands the texture from three to four, five, and more parts. The style unites the consort style of earlier eras, while suggesting also the French and Italian instrumental idioms that were popular in Purcell’s lifetime. The music is dark, lively, exuberant, and melancholy by turn, marvellous in its variety. Fretwork’s ensemble is faultless and beguiling throughout.

Die Kunst der Fuge / Bach, Johann Sebastian

Although many authorities agree that Die Kunst der Fuge /The Art of Fugue was likely written for a keyboard instrument, albeit in an ‘open’ score, Bach’s monumental collection of fugues based on a four-bar subject lends itself to performance by ensembles. Instrumental performances, such as this recording by Il Suonar Parlante, illuminate the intricacy of Bach’s counterpoint, as the contrasting sonorities of viols and fortepiano give voice to the individual musical lines. The nature of the viols’ sound is evocative of the human voice, adding an eloquent vocal quality to the fugues, contrasting with the more percussive effect of the fortepiano. Il Suonar Parlante’s approach to Bach’s Art of Fugue offers a counterpart to that of Jordi Savall’s Hesperion XX, whose 2001 recording utilises a remarkable array of instruments.

Die Kunst der Fuge : BWV 1080 / Bach, Johann Sebastian

Die Kunst der Fuge : BWV 1080 / Bach, Johann Sebastian

This is a remastered reissue of a recording made in France in 1986. Jordi Savall, Roberto Gini, Christophe Coin, and Paolo Pandolfo (viols) are joined by cornetto (Bruce Dickey), trombone (Charles Toet), oboe da caccia (Paolo Grazzi), and bassoon (Claude Wassmer). The contrast between the string, woodwind, and brass timbres again illuminate the complex contrapuntal structures of Bach’s music, giving each line a unique character. Compared with more recent approaches to the Art of Fugue, Savall’s tempos sometimes seem sedate. Possibly the acoustic in the collegiate church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Roquemaure also influenced this magisterial approach. Once again, the recording demonstrates the flexible evocative sound of the viol.