[Transcript]

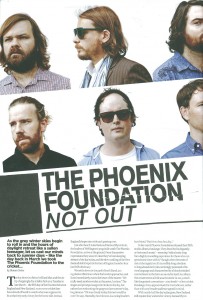

The Phoenix Foundation: Not Out

As the grey winter skies begin to roll in and the hours of daylight retreat like a sullen teenager, let us cast our minds back to sunnier days – like the day back in March we took The Phoenix Foundation to the cricket…

by Duncan Greive

The sky above is a fierce, brilliant blue, and the air lip-chappingly dry at Eden Park on a Tuesday in late March — the fifth day of the final test between England and New Zealand. I0,000 or so cricket fans have skived off work to watch what was supposed to be a relatively early victory for the home side. Instead, England’s hopes rise with each passing over.

Just after lunch Luke Buda and Samuel Flynn Scott, the leaders of Wellington’s prog-indie outfit The Phoenix Foundation, arrive at the ground. From the pensive expressions they wear, it’s clear they’ve been keeping abreast of the day’s play, and the slow curdling of the New Zealand side’s hopes in the face of England number four Ian Bell’s obstinacy.

We settle down in the park’s South Stand, at a regulation third man when the bowler approaches, and Scott immediately cuts to the heart of the matter. “We really need another wicket at this point, I reckon.” The singer and principal songwriter looks to the sky, but rather than welcoming the gorgeous late summer’s day, he grimaces. “If it was cloudy today, this test would be over,” he says. Humidity, Scott knows, is a swing bowler’s best friend. “But it’s so clear, hot, dry…”

In late April, Phoenix Foundation released their fifth studio album, ‘Fandango’. They described it, elegantly, as ‘test match music’ – meaning “ridiculously long but a highly rewarding experience for those who can spend some time with it”, though other elements of test cricket apply too. It’s incredibly long, obedient to long-abandoned rules, seemingly possessed of its own language and characterised by a bloody-minded commitment to the form as an end in itself. An album this ornate seems a little anachronistic in 2013, much like the genteel conventions — a tea break! — of test cricket. ‘Fandango’, then, appears made for true believers, rather than with any broader audience appeal in mind.

With nearly half the day‘s play gone, New Zealand still require four wickets for victory. Samuel Flynn Scott is absolutely right. We really, really need another wicket. As tense as the situation is, though, there’s no place any red-blooded New Zealand sports fan would rather be. The Phoenix Foundation, despite their impeccable artsy credentials — albums on Flying Nun, film soundtracks, beards — are bonafide sports fans.

Flynn Scott’s cricketing prowess was limited by a slightly lazy eye, which he says “tums on and off every I0,000th of a second.” Even in his pomp, though, he didn’t terrify opposing batsmen. “I’m more of a gammy slow-medium bowler,” says Scott. “More of a Chris Harris. But now I can’t even bowl.” Instead the band sport is now table tennis. “We’ve all got quite good at it,” says Scott, with a trace of uncertainty.

What they have undeniably got better than quite good at is making albums. Since forming at Wellington High School – an institution which has produced a disproportionate amount of the capital’s creative talent – in 1997, the band have grown the determinedly old-fashioned way. That means waiting two or three years between albums, putting out oddball solo records, and building an audience by playing live. Buda, in particular, resents having to apologise for what a decade ago would have been an entirely unremarkable approach to band life.

“Do you read that guy Bob Lefsetz? He’s saying ‘the album is dead’!” spits Buda, unprompted. “And I think ‘no!’ Because it’s not dead to me.” Lefsetz is an attorney and writer known for pouring petrol on the music industry’s woes, and generally calling out its most sacred totems. Like, say the ‘album’, a hoary relic he recently called “an antiquated construct that fits the modern era not at all but it sustains because it’s the only way artists and labels have figured out how to make money.”

To paraphrase Buda himself, that may be true, but it’s not true for the Phoenix Foundation. Mostly because if making money is a big motivator for the band, they’re not particularly good at it. Later in the afternoon, while lamenting commercial radio’s disinterest in their music, Buda notes that he’s “struggling to pay the rent.” Flynn Scott’s housing situation is no better. The opening song on Fandango, a wry synthesiser glide named ‘Black Mould’, candidly discusses that old rock’n’roll warhorse, stachybotrys — a toxic, asexually reproducing, filamentous funghi.

“Black Mould — it’s so much about the New Zealand experience to have a really mouldy house that’s making you sick,” says Flynn Scott. “That’s actually killing you. But, you know, no one wants to think about that.”

The song wearily glories in the mundane anxieties common to the damp, depressed villa dwellers of New Zealand, but despite its very literal lyrics, it’s confusing listeners. Surely it’s not actually about mould?

“I’ve had a few interviews where people have said ‘what is it – is it a metaphor?” says Flynn Scott. “And it’s not a metaphor! It’s just exactly what was going on in my house when I wrote it. We were just really stressed out by having this baby, and having a mouldy bathroom. Dehumidifiers going all the time. Nothing ever drying. It’s raining outside. And you’re like ‘should I use the drier? Can I afford to use the drier?’”

“It’s just reality that song,” he adds. “It’s not pretend reality, like junkies, gangsters and guns.” Notwithstanding that for good-sized portions of the world junkies, gangsters and guns are every bit as real as mould, he has a point. There is something endearing in the ordinariness of the song’s subject matter, and the way the band find elevating beauty growing in the bathroom. We’re a long way from watery Wellington today, though. The sun beats down mercilessly on the tiring New Zealand bowlers, and the crowd who have come to watch them The session has become almost comically bad for New Zealand.

In the stands, Flynn Scott is cursing like a sailor. When he calms down, he picks up Buda’s lead about commercial radio’s lack of interest in the band, and their correspondingly small checks from APRA, the songwriting association which receives and distributes a percentage of radio revenues. Once again, Flynn Scott has a theory. “I’ve never understood why governments don’t just impose a 45% New Zealand music quota,” he says. “Because it would just mean a huge amount of revenue staying in New Zealand. Radio stations say it will kill them, but why? Are people going to stop listening to the radio because of the music they play?”

His bandmate is not convinced. “I’m surprised by this rationale Sam,” says Buda amiably. “There just isn’t enough music made in this country to sustain that.” As if to back up his point, the local crowd’s response to the endless, glorious singing of the touring English fans known as the ‘Barmy Army’ has been a single rendition of our turgid national anthem ‘God Defend New Zealand’. It was woeful.

After a quiet moment, suddenly Buda sits straight up. “I do have to get out of the sun now guys,” he says forcefully. “I just had a bit of a ‘whoa’ moment.” Perhaps betraying their Wellingtonian inexperience with prolonged, profound sunshine, neither has worn a hat, and only Flynn Scott has sunglasses. Between the two of them, there is no sunscreen for all that pasty white skin. We decamp further up the terrace. Alongside the West Stand and back of square leg, we find shade and a breath of breeze.

Buda is immediately revived. Warming to his theme of what he sees as the barren wasteland that is commercial radio in New Zealand, he contrasts it with the musical culture of our on-field opponents. “You get the vibe that the British just care more about music. We played at Glastonbury – and that place was a fucking hell hole – and people still flocked there. It smells like shit,” he says, before his bandmate interrupts him.

“But a thousand people showed up to watch us in the mud! We were the first band on, you had to wade through mud, we were nowhere near the campground. We were pretty stoked that people actually showed up. But they do. You hear anything about a band being good and people just show up,” Flynn Scott marvels. “I think they believe in the awesomeness of going to see live music,” says Buda, leaving unspoken the implication that New Zealanders, well, don’t.

They can be a glum pair, at times. It’s as if the process of putting out consistently acclaimed albums for consistently middling reward has worn them down. Made them a little bitter. None of it comes through on Fandango, which is big-hearted, richly textured, and generous to a fault. But in conversation the band often veer toward what’s wrong with the world. It would be easy to mistake them for a pair of grumpy old men, carping on a sunny day. But maybe they were just hungry?

A while earlier they had dispatched their record company rep to a local cafe in search of food. When I complimented them on their specific and well-judged instructions – they hadn’t been to Eden Park before, but knew the best local take-out food – Buda fixed me with a hard stare. “Can’t you tell we know where to eat?” he says, patting his healthy belly. When the pies arrive they are devoured with great relish.

“This is an amazing pie,” says Flynn Scott. “This pie’s making me feel human again,” says Buda. They’re clearly pie experts. I ask where these pies sit in their pie rankings. “Fridge pies would be pretty high up, actually. Pretty high up in the global pie… chart,” laughs Buda. “Good NZ pies are – you get some pretty bad pies around the world. Or no pies at all,” says Scott. “Can you imagine that!” says Buda, shaking his head.

The tea break looms. The deflation in the crowd, the baying barmy army – and our own disinterest – convey it all. Out of the blue, in the midst of the final over before tea, Neil Wagner tempts Bell into a push. Southee scoops the catch low at third slip, and the whole ground erupts. “Yeeeaarrrggh!” roars Flynn Scott, out of his seat, fist flailing. Game on.

We move back down, closer to the action, willing the 20-minute adjournment to speed by. Alongside us an elderly chap in the violent red and yellow shirt of the Marylebone Cricket Club overhears our conversation and inserts himself. He first points out the towering figure of former England quick Bob Willis on the edge of his seat a few metres away, then turns to music, regaling us with tales of seeing The Who with Stereophonics (“fantastic”, apparently) in support. Buda and Flynn Scott gamely feign interest until he heads back to the bar. The band have occasionally been accused within New Zealand of epitomising that dad-rocker tradition, of over-venerating the grand old men of Mojo magazine. If it were ever true, that sound has all-but vanished from Fandango.

The most prominent instrument is multi-tracked synthesiser. They’ve leaned on the instrument in the past, but never with such immersion. While Buda has metal roots (sample early music discourse: “which Kirk Hammett solo had the coolest hammer on/hammer off finger tapping?”), it’s he who has lead the band deepest into this vast, astral sound-world. The breakthrough record was Air’s compilation ‘Premiers Symptômes’, the constant soundtrack to stoned teenage journeys through the hills of Wellington in Buda’s 1984 Honda City.

While the rest of the band has more conventional upbringings, Buda is Polish, and his journey to New Zealand involves escape from behind the iron curtain at a young age. Flynn Scott tries to get him to talk up this unavowedly glamourous episode, but Buda shrugs it off. He was too young to remember the life they left behind, and is happier talking about the importance of Dire Straits and Genesis records in his television-less household.

The players return to the field. Babyfaced bowler Stuart Broad comes to the crease. In a recent piece he wrote for the Guardian, Flynn Scott memorably fantasised about “him accidentally ending up on the wing for England against the All Blacks. In this inter-sport dream, Broad is horrifically tackled by Ma’a Nonu and will never bowl again.” Sadly, Broad can bat, and displays a hitherto unknown capacity for stoic defense.

Early on, Buda and Flynn Scott sense which way the wind is blowing and wonder how they can contribute to our team’s flagging spirits. “Do you think it’s time for some quite aggressive sledging?” wonders Flynn Scott, while Buda attempts a slow clap to accompany Trent Boult’s lengthy run up. It is, I feel quite comfortable in saying, an unmitigated disaster, and one he tries on three occasions – each louder and lonelier than the last – as if to make certain beyond all doubt that no one will join in.

Before he can attempt a fourth, their record company minder arrives. It’s time to head away to the next interview. In a little over a session, which should have seen wickets falling regularly and massed public triumph, nothing particularly happened, despite the toil and sweat of the New Zealand side. It’s probably best not to view that as yet another sporting metaphor for the band’s career.

Sourced from Rip It Up, No. 353, June-July 2013. Used with permission.