The Land of Tara and they who settled it, by Elsdon Best

The story of the occupation of Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara (the great harbour of Tara) or Port Nicholson by the Maori.

About the time that the Norse seafarers were exploring the new found coasts of far Vinland, the Harbour of Tara, lay lone and silent in the south land. From the storm lashed cape, of the far north to the rugged island outposts of the south, the smokeless lands awaited the coming of man. The far stretching forests, the lakes, rivers and seas, the plains, vales and mountains, were occupied only by the offspring of Tane and Tangaroa, of Punaweko and Hurumanu. The fair isles of the south had, through countless centuries, slowly ripened for occupation by man; man the destroyer, and man the maker.

The story of the discovery and settlement of Port Nicholson, or Wellington Harbour, is closely connected with that of the discovery and settlement of New Zealand by Polynesians, hence we give a brief account of those happenings, both due to the energy and skill in navigation of the old-time Polynesian voyagers. In most cases we are able to assign an approximate date for historical occurrences connected with the Maori Tradition, but in regard to the time of the discovery of these isles we are at fault, for apparently no reliable genealogy from the discoverers has been preserved. From other evidence, however, we can assume that such discovery was made not less than forty generations ago, or say the tenth century.

The first voyagers to reach these isles are said to have been two small bands of adventurers from Eastern Polynesia, who, under the chiefs Kupe and Ngahue (also known as Ngake), reached these shores in two vessels, probably outrigger canoes, named 'Mātāhorua' and ' Tawiri-rangi.' We are told that Kupe was accompanied by his wife and children,

Poupaka = Mowairangi | Pouturu = Tahapunga | Aparangi=Kupe | and this is probably correct for the Polynesian Voyagers often carried their women folk with them on deep sea voyages, even as Maori women accompanied their men on war expeditions. The wife of Kupe, one Aparangi by name, was a grand-daughter of Poupaka, whom tradition claims to have been a famous and bold navigator, though tradition claims too much for him when it dubs him the first deep-sea sailor, for at that period the Polynesians had sailed far and wide athwart the great Pacific Ocean. |

However, it is well to extol one's own ancestors. Part of the tradition reads:-

"It was Poupaka who began sailing abroad on the ocean, when all others feared to do so on account of their dread of Tawhirimatea and his offspring (personified forms of winds), hence the following saying became famous:-' Tutumaiao Tawhirimatea, whakatere ana Poupaka,' as also this:- 'Tutu te aniwaniwa, ha tere Poupaka i te uru tai.' "

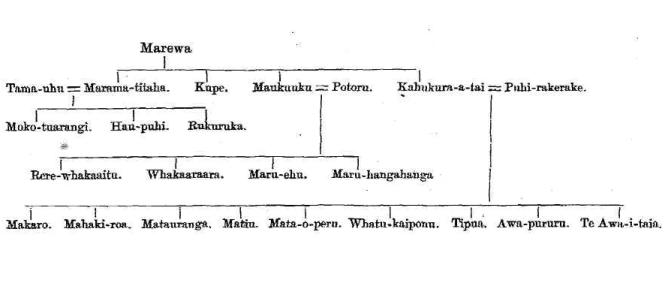

The story of the coming of Kupe is encrusted with myth, and there are several versions as to the cause of his coming. One of these versions is to the effect that his daughter Punaruku was slain while bathing at Wai-o-Rongo, at Rarotonga, where she was attacked and, as our mythopoetic Maori puts it 'carried off to Tai-whetuki,' the house of death. Kupe pursued the monster who had slain his daughter across far ocean spaces until he finally caught and slew him at Tua-hiwi-nui-o-Moko, in Cook Straits, assisted by his nephew Mahakiroa. Others who assisted him were his relatives Tipua, Kaiponu, Awa-pururu, Te Awa-i-taia, Maru-hangahanga, Maru-ehu, Hau-puhi, and his attendants Komako-taa, Popoti and Ahoriki. The following table shows the position of persons mentioned in this tradition in regard to Kupe. It was given by Te Matorohanga (this is the 'sage' of our Memoirs, Vol. III. and IV. editor) of Wai-rarapa, and shows Matiu and Makaro as nieces of Kupe, instead of daughters as they appear in another version :

After a weary voyage across the southern ocean, one day a low hung cloud attracted attention. Quoth Kupe, " I see a cloud on the horizon line. It is a sign of land." His wife cried, " He ao ! He ao ! " (A cloud! A cloud!) That cloud betokened the presence of land, rest and refreshment for cramped and sea racked voyagers. The two vessels made the land in the far north, where the crews remained for some time, after which they continued their voyage down the east coast of the North Island. On the way down Kupe named Aotea island (the Great Barrier), and the mainland was named Aotearoa, after the white cloud greeted by his wife Hine Te Aparangi (ao tea = white cloud). The longer name may thus be rendered as Greater Aotea, or Long, or Great Aotea. When Kupe returned to Hawaiki from these isles, the people asked him:- "Why did you call the new found land Aotearoa, and not Irihia or Te Hono-i-wairua, after the homeland our race originated in ? " But Kupe replied :- " I preferred the warm breast to the cold one, the new land to the old land long forsaken."

Hori Ropiha, of Napier, remarks that Kupe and Ngake (Ng-ahue) distributed their children all round Aotearoa. Their food was wind alone, and in these days those folk bear the aspect of rocks. The following lines from an old song refer to these occurrences :-

"He uri au no Kupe, no Ngake

E tuha noa atu ra kia pau te whenua

Te hurihuri ai ko Matiu, ko Makaro."

The Maori, with his mythopoetic mind, would not state baldly that certain places, rocks, islets, etc., were named after these personages.

Hori goes on to relate the old myth that Kupe left here the obstructions to travellers by land, such as the ongaonga (nettle, Urtica feros), the tumatakuru (Disearia toumatou), and papaii (Aciphylla), which were burned in after times by Tamatea of Takitumu, an immigrant from the Society Group. Again we refer to a reference in song:-

" Nga taero ra nahau, e Kupe!

I waiho i te ao nei."

(The obstructions there, by thee, O Kupe! left in the world.)

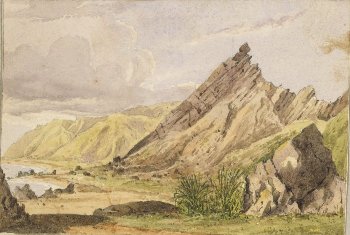

Another old local myth is to the effect that our harbour was at one time a lake in which dwelt two monsters named Ngake and Whataitai (syn. Hataitai, the native name of Miramar peninsula). These two beings attempted to force their way out of the harbour. Ngake succeeded by forming the present entrance, but Whataitai failed in a similar attempt at Evans Bay. Hence he assumed the form of a bird and betook himself to the summit of Tangi-te-keo (Mt. Victoria), where his shrieks were plainly heard.

In the quaint conceit in which the North Island is called Te Ika-a-Maui (Fish of Maui), Wellington Harbour is styled the right eye of the fish, and, Wai-rarapa Lake the left eye.

Leaving Wellington Harbour our seafarers moved on to Sinclair Head, where they camped for some time in order to lay in a stock of sea stores in the form of dried fish and shellfish, for which that place has ever been famed in Maori annals. Here also they procured quantities of rimurapa (D'Urvillea utilis), the great wide stems of which they utilised as vessels (poha) in which to store and carry their dried foods, a use to which this giant seaweed was frequently put by the Maori. It was on this account that the party named Sinclair Head Te Rimurapa. The point near this head known to us as the Red Rocks is called Pari-whero, or Red Cliff by natives, on account of the peculiar colour of the slate rock in that vicinity. Here are two old myths concerning the origin of such redness. One is a somewhat prosaic one, namely that Kupe had his hand clamped by a paua (Haliotis) so severely that the flowing blood stained the surrounding rocks, as also the ngakihi (limpet, Patella) of the adjacent waters. The other version sounds better, and is to the effect that Kupe left his daughters at this place while away on one of his exploring trips. He was away so long that the maidens began to mourn for him as lost to the world of life. They lacerated themselves after the manner Maori, even so that the flowing blood stained the rocks of Pari-whero forever.

Moving on from Sinclair Head the rovers stayed a while at Owhariu, and then went on to Porirua Harbour. While at this place one of Kupe's daughters is said to have found on the beach at the northern side of the entrance a stone higly suitable for a canoe anchor, hence it was placed on board 'Matahorua' to be used for that purpose. This stone anchor was named Te Huka-a-tai because such is the name of the kind of stone it was composed of. On account of this occurrence Kupe left one of his stone anchors at Porirua; one named Maungaroa because he had brought it from, a place named Maungaroa at Rarotonga in the Cook Group. This anchor is said to have been carefully preserved for centuries, and is now in the Dominion Museum, Wellington. Long years ago old Karehana Whakataki of Ngati-Toa conducted the writer to a spot near, and on the eastern side of the railway line at Paremata, a few hundred yards north of the bridge, and there showed him Kupe's anchor. It is a heavy and unwieldly waterworn block of greywacke, of a weight that casts a doubt on the assertion that it was used as a canoe anchor, certainly it could not be handled on any single canoe. A smooth faced hole through one corner of it is said to have been where the cable was attached, but it bears no sign of human workmanship. This change of anchors is said to have been the origin of the name Porirua, but the statement is by no means clear. We know of no meaning of the word pori that throws any light on the matter.

The voyagers went to Mana Island, off Porirua Heads, where Mohuia suggested that the island should be so named as a token of the mana (authority, etc.) of the voyagers, which was agreed to. This name origin is by no means clear, for the name of the island is pronounced Mānă, whereas in the other word both vowels are short, mănă, and the correct rendering of vowel lengths is most essential in Maori. A point or headland at Ra'iatea island is known as Mānā, and it may be thought that the name is a transferred one that has been corrupted, but this sooms doubtful. A native writer, however, seriously enough, gives the island name as Manaa to show that the final vowel is long, but as this method of denoting long vowel sounds is never consistently followed by any native, we are still in doubt concerning the first syllable.

From Mana Island the explorers crossed Cook Straits, went down the West Coast of the South Island, and, at Arahura, discovered greenstone, a very important occurrence in Maori history, of such value was that hard and tough stone to them in the manufacture of implements. Here also at Arahura the explorer Ngahue is said to have slain a moa at or near a waterfall in the river. On his return home to Hawaiki he reported that the most remarkable products of Aotearoa were greenstone (nephrite) and the moa.

The explorers coasted both islands ere they left on their return voyage, but these further adventures do not concern our harbour story. On his return Kupe visited Rarotonga, Rangiatea, Tonga, Tawhiti-nui, and Hawaiki, that is Titirangi, Whangara, Te Pakaroa, and Te Whanga-nui-o-Marama, and at these places gave an account of his voyage, and of the moisture laden land he had discovered at tiritiri o te moana, that is, in the great expanse of the southern ocean. Here Kupe the voyager passes out of our story.

The interesting feature of this voyage is that the discoverers of these isles came to a lone land. They found here no human inhabitants, according to tradition, but when the next Polynesian voyagers reached these shores they found a considerable part of the North Island occupied by man, showing that probably not less than eight or ten generations had passed since the time of Kupe.

The Coming of the Mouriuri or Maioriori folk (pp. 7-9)

The people found here by the first Maori (Polynesians) to settle in New Zealand, are generally alluded to as Maruiwi, though that was not a racial name for the people, but merely that of a chief, and, later, of a tribe. Three famous pu korero, or conservers of tribal lore, of the early part of the last century, named Tu-raukawa, Nga Waka-taurua, and Kiri-kumara, stated that the Chatham Island natives were known as Mouriuri, not Mooriori, and we know that those folk were descendants of the original inhabitants of the North Island, or Aotearoa. There is no explanation as to whether or not the Maori bestowed that name upon them, either prior to their leaving these shores, or on the occasion of the islands being discovered by Europeans and visited by Maori adventurers some time later. Presumably the alleged corrupt form of Mooriori (so spelled in a Maori manuscript) was obtained either from the natives of the Chathams or from Maori experts (to be corrupted later). Such primitive peoples seldom have a racial name for themselves, and the racial name of Maori for our New Zealand natives was apparently not used as such formally, for none of the earlier writers mention it.

In giving the positions of some of the aborigines of Now Zealand at the time they left the Rangitikei district to settle at the Chathams, the above experts remarked that the persons named were the principal men of the Mouriuri folk.

According to traditions handed down by the Maori the original settlers of New Zealand were descendants of the crews of three canoes that came to land on the Taranaki coast and settled in the Urenui district. These folk had been driven from their home land by a westerly storm, but must apparently also have been driven southward, to reach these shores. They may have drifted hither from the New Hebrides or the Fiji Group, for they described their home land as having a much warmer climate than that of New Zealand. That land they called Horanui-a-tau and Haupapa-nui-a-tau, which are unknown to us as island names, and their three vessels were called Okoki, Taikoria and Kahutara.

Maori tradition states that these early settlers were an ill favoured folk, dark skinned and ugly, tall and spare, with flat faces and flat noses, upturned nostrils, projecting eyebrows and restless eyes. Their hair was harsh and stood out, or was bushy; an indolent folk and treacherous; extremely susceptible to cold. They erected no good houses, merely rude huts, wore no garments in summer, but merely leaves, and rough woven capes in winter. They lived on forest products and fish, and did not understand the preserving of food. Their weapons were the huata (long spear), the hoeroa, the kurutai, and the tarerarera (whip thrown spear) ; another was the pere or kopere, to project which they bent a piece of manuka (wood), using dog skin for cords.

This description does not seem to fit the Fijian, and the origin of our first settler remains a mystery. A few alleged Mouriuri words preserved are of Polynesian form, but the description of their persons points to a Melanesian origin. They apparently differed much from the Maori, and may be the origin of the Melanesian peculiarities seen in many of our natives, a fact noted by a number of writers.

These Mouriuri, or Maioriori, or Maruiwi folk, were found occupying the northern half of the North Island by the first Polynesian settlers to arrive here. Their settlements extended as far south as Oakura, or, as another version has it, Wai-ngongoro, on the west coast of the island; and about as far as Mohaka, in Hawkes Bay, on the east coast. After the arrival of the Maori-Polynesian settlers

some of the original people settled in the Napier district, the inner harbour at that place-being named after one of their, chiefs, Te "Whanga-nui-a-Orotu. We shall see, in the days that lie before, that a remnant of these people, known as Ngati-Mamoe, were pushed southward in later times, and took, refuge at Wellington, prior to occupying the South Island.

The incoming Maori seem to have rapidly increased in numbers, owing to the fact that they obtained numbers of women from the aborigines to supplement the number of those brought from Polynesia. As time rolled on this people of mixed descent waged relentless war on the original people, until the renmants of the latter were found only in the wild interior, such places as Maunga-pohatu and Taupo. A few fled to the Chatham Isles, as remarked-above. (These Chatham Islanders called themselves Maoiriori when Europeans first went among them). But we are anticipating, and must now bring the Maori from the sunny isles of Eastern Polynesia.

The coming of the Maori,

The Polynesian Voyager Toi reaches New Zealand. (p.9)We have here no space for the whole of this most interesting tradition, and can give but the bare outlines of it. In the time of Toi, who flourished at Hawaiki, Society Isles, thirty-one generation ago, a number of vessels were carried away by a storm from that island. Among the crews were two near relatives of Toi, one of whom, Whatonga, was his grandson. Many of these ocean waifs, including-Whatonga, did not return to the home island, hence Toi sailed in search of his grandson. He visited a number of islands, and sailed as far west as Pangopango, at Hamoa (Samoa), and found some of the castaways at that group, but not his own relatives. He then sailed down to Rarotonga in the Cook Group, but again met with disappointment. He now resolved to go further afield, and said to Toa-rangitahi, a chief of Rarotonga: "I now go forth to seek the mist moistened land discovered by Kupe. Should one come in search of me, say that I have sailed for land in far open spaces, a land, that I will reach or be engulfed in the stomach, of Hine-moana." (Hine-moana, personified form of the ocean)

Even so Toi the voyager, sailed from Rarotonga in his vessel named ' Te Paepae-ki-Rarotonga,' and boldly went forth on the great expanse of ocean that rolls for 1500 miles between that isle and New Zealand. The story of how he missed this land, but discovered the Chatham Isles, need not be told here, sufficient for us that he eventually reached the land of Aotearoa. He stayed some time with his crew at Tamaki (Auckland isthmus) among the Mouriuri folk of that place, then the party proceeded to the Bay of Plenty and settled at Whakatane, where his descendants are still living, and point out the site of the home of Toi, the voyager from far lands - one of the gallant old-time sea rovers who laid down the ara moana or sea roads, for all time.

The coming of Kurahaupo.

Whatonga reaches New Zealand in his search for Toi. (pp.9-11)Some time after the departure of Toi, from the home island in Eastern Polynesia, Whatonga returned to find that Toi had sailed to range the wide seas in search of him. Whatonga resolved to go after him, and, having prepared his vessel, 'Kurahaupo,' he carefully selected a crew of hardy deep sea sailors, and bade farewell to his home for ever. As the sacred ritual performance over his vessel closed, Tu-kapua said to him:- "O son! Fare you well. You will yet find and greet your elder. He ihu whenua, he ihu tangata." And then, as dawn broke, Kurahaupo was hauled down to the sea and launched on the broad, heaving breast of Hine-moana.

In course of time, after divers wanderings to and fro across the wide seas, Kurahaupo arrived at Rarotonga, where one Tatao told the voyager that Toi had, in the month of Ihomutu, sailed for the humid land discovered by Kupe. And so, after due preparation, in the month of Tatau-urutahi (October), Kurahaupo sailed out from the land and lifted the long, rolling water-ways to Aotearoa.

Kurahaupo made her landfall in the far north, and after a short sojourn there, her crew ran down the west coast as far as Tonga-porutu, where Whatonga learned from the Mouriuri folk that a stranger from far lands, named Toi, had settled on the east coast. Our voyagers then sailed northward again, rounded the North Cape, and ran down the east coast, finally reaching the home of Toi at Whakatane.

Having sojourned some time with his elder, Whatonga again manned his sea going canoe and went to seek unoccupied lands on which to settle, finally making his home at Nukutaurua. This party obtained a number of women from the aborigines of the Bay of Plenty district. Whatonga was happy in the possession of three wives.

Said Toi:-" Go to the eastern side of the island, which is but thinly settled, and seek a home on coastal lands, that you may possess two good baskets, that of the ocean and that of the land, inasmuch as food is the parent of the orphan, of women, and of children. Quarrel not with such peoples as you may encounter, let peace encompass the land, that women and children may walk fearless and unharmed abroad."

The party of Whatonga was increased in numbers by some of Toi's folk joining it, as also by the women they had acquired from the aborigines living at Moharuru, a place now known as Maketu. On arriving at Huiarua our travellers resolved to remain there for some time. The hut of Whatonga at that place was constructed largely of trunks of a small tree fern, and was named Tapere-nui-a-Whatonga, After some time the travellers moved on to Maraetaha, and finally to Nukutaurua, where a permanent settlement was made at a place called Taka-raroa.

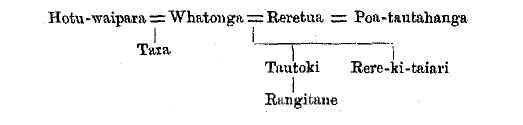

In after days, when Whatonga felt the weight of years, he resolved to despatch his sons to explore the country to the southward to examine it and seek desirable lands whereon they might settle. Those sons were the half-brothers Tara and Tautoki, the full name of the latter being Tautoki-ihu-nui-a-Whatonga.

Exploration of Wellington district by Tara and Tautoki. (pp. 11-13)

Whatonga said to his sons, Tara and Tautoki:- "O sons, go forth and examine the land. Take but few companions with you, and leave your women and children here, that you may travel quickly."

Then were carefully chosen the men to accompany them, in numbers thirty twice told. The party came by way of Te Wairoa to Heretaunga (Napier district), then occupied by a tribe of aborigines. After an examination of that district, they came on to Rangi-whaka-oma (Castle Point), thence to Okorewa (in Palliser Bay), thence to Para-ngarehu (Pencarrow Head), from, which place they explored the surrounding district, and Tara remarked, "This is a place suitable for us."

They then went on to Pori-rua, to Rangi-tikei, thence up the river to Patea, to Tongariro, to Taupo, whence they struck across to Titi-o-kura, and returned by way of Mohaka and Te Wairoa to Nukutaurua, to their home.

On the return of the party of Tara, Whatonga rejoiced in once more seeing his sons, for they had been absent nearly a year. Tara and his brother, with the other members of the exploring expedition, now began to relate their experiences, and to describe the lands they had seen, the hills and mountain ranges, the rivers, lakes and harbours thereof, as also the plains and forests, together with the lie of the lands in regard to the sun and prevailing winds.

Whatonga enquired:-" Which do you consider the most desirable place to settle at, as in regard to food supplies? "

Tara and Tautoki explained: - " At the very nostrils of the island, where are situated the two isles we have heard of as having been named by Kupe after his daughters Matiu and Makaro. The largest island (now Miramar peninsula) is situated to the southward, where the two channels connect with the vast expanse of Hine-moana (the Ocean maid. Personified form of the ocean), but only a numerous people oould occupy and hold this large island (ma te umauma tangata tenei e noho). The two small islands are desirable places whereon to settle; they can be reached only by canoe, and the larger one (Somes Island) has fairly good soil, wherein food products might flourish. The isle to the east of this one is a bare place, with inferior soil (Ward Island)."

Whatonga enquired :-"What sort of a place is the large island you speak of, in regard to the cultivation of the kumara, (sweet potato Ipomoea batatas) ? "

Tara replied:-" The soil is good, being a loam, vegetation flourishes and is not stunted in growth ; water soon flows off it."

Whatonga remarked:- "On dry lands a damp season is needed to cause crops to flourish."

Said Tara:-" Just so ; but some sheltered parts are suitable."

Again Whatonga enquired:-" Are the channels deep, did you observe, at low tide ? "

Tara answered :-" One of them, the channel on the eastern side, is deep (the present entrance). In the entrance channel on the western side (now an isthmus) a sand ridge extends from the ocean right through to the harbour. It seems to me probable that the western entrance channel may yet fill up and be raised."

Whatonga asked:-" Are there no rock-reefs at the seaward end, outside ?"

" No! The rocks are congregated near the cliffs (at Lyall's Bay)." Tara continued:-" The other island (South Island) looked quite near, and is apparently about a day's voyage distant. The harbour on the western side (Porirua) is a fine expanse of salt water, and sheltered ; we observed that the hills shelter it from the winds. The soil of its lands is a loam; and the entrance to the harbour a good one, but it is not a desirable place for a few people to settle at, it can be safely occupied only by a numerous folk. There is an island lying outside the entrance (Mana Island), which, if a canoe started at dawn, we thought might be reached by noon. It seemed a fine island, from what we saw of it, with a well exposed, fair surface, but the food of winds. Still it would be an excellent parent (place of refuge) for women and children.

"The fresh-water sea on the eastern side of the mountain range (Wai-rarapa Lake) is surrounded by open land; its shores are swampy, but it is apparently a good district for food supplies. Streams from the mountain ranges flow into it; it has such ranges on its eastern and western sides (The Aorangi and Remutaka Ranges), as also some lower ridges to the eastward. The mountain range to the westward is rocky, the soil thereof stony and poor; snow lies thereon but not permanently. That range is one of the shoulders of the island, and extends right down to the ocean near our encampment. Streams from the eastern and western ranges flow into the lake, the outlet of which is but a small stream ; there is a small islet just off the eastern shore. It would require a large number of people to occupy and hold this district, as also the lands round the first harbour I spoke of, but the soil is good, in some places a loam, in others black soil, in yet others somewhat stony. The plain lands we saw are fine and have a good exposure.

" There is another sheet of salt-water much nearer here (? Napier Harbour), which receives certain streams from the interior, but those lands would require many people to settle them. However, I have claimed the harbour at the point of the island as a resting place for us."

"It is well," said Whatonga, " But do not attempt to occupy much of the land you saw, for you are not numerous enough to do so. It will be well, however, to hasten and lose no time in going to settle on the lands of the salt-water sea (Wellington Harbour), and of the fresh-water sea (Wairarapa Lake)."

This was agreed to, and Whatonga accompanied his sons and their followers southward to take possession of and settle on the shores of the harbour discovered by Kupe. Some of Whatonga's men were left at Nukutaurua to hold those lands, and to protect the people who were dwelling in the open (not in fortified villages).

p. 13 continued - Settlement of the Wellington district.

Korero o te Wa I Raraunga I Rauemi I Te Whanganui a Tara I Whakapapa