“Dying faces are the colour of soiled linen. It’s the eyes which shine, as if the world around the person who is dying has brightened itself, so it’s fully seen and felt and known.”

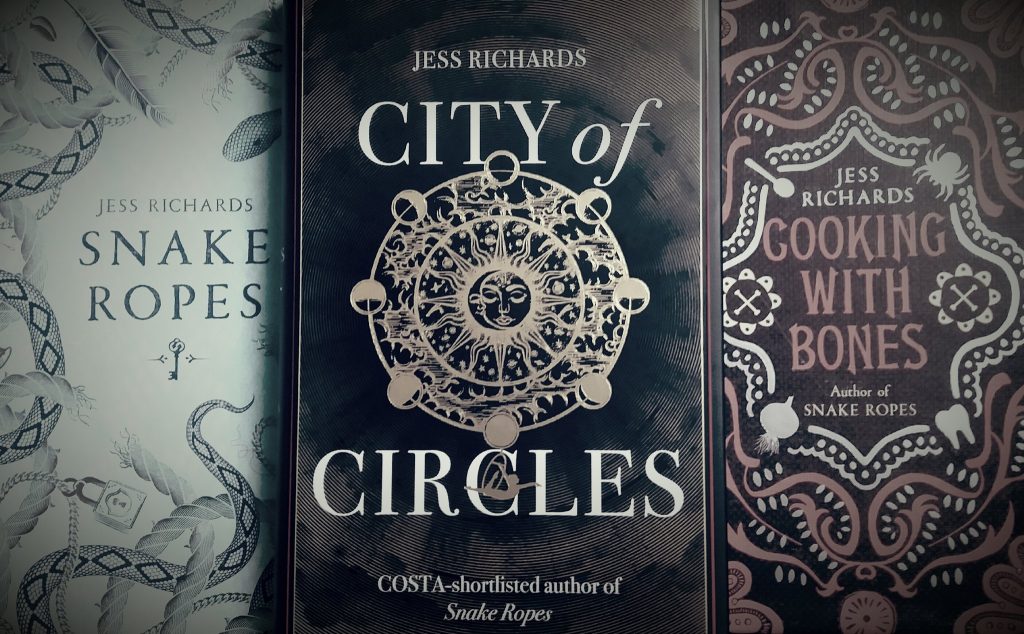

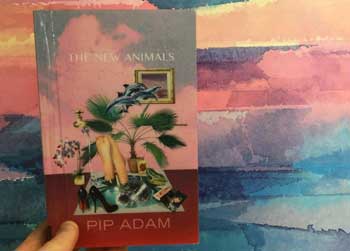

So begins City of Circles, the third novel by acclaimed Wellington author Jess Richards. Richards’ work has been described as “brilliantly peculiar” and “a cornucopia of secrets and surprises”, with her debut novel Snake Ropes being nominated for the Costa First Novel Award, the Scottish Book Awards and the Green Carnation Prize. City of Circles tells the story of orphaned circus performer Danu as she negotiates grief, love and the mystery at the heart the fantastical city of Matryoshka . . .

Your work has been compared to Angela Carter and Erin Morgenstern, both of whom use circuses as key elements in their work. What do you think it is about circuses that continue to appeal to readers and writers?

Circuses have great potential to be made magical in fiction, because of their potential to appeal to all the senses, and also their rich history and traditions. They’re archetypal places of wildness and strangeness – performance and storytelling, which speak to our very human need for wonder. This is so often lacking in the ‘real world’ – as adults, we often lose sight of our desire for magic and strangeness. Within stories, we can find a parallel world to disappear into, between mundane daily rituals, tasks and chores. The people within circuses can be strange in so many ways – from the bearded lady to the cartwheeling clown, from the strong man to the contortionist. These slightly off-kilter people can be unique and intriguing characters to read and write about. The ordinary, distorted. The usual, made strange.

In Snake Ropes, the world of the story has been described as intentionally minimal in order to create the feeling of an “insular society”. How did creating Matryoshka and the world within City of Circles differ to this?

After writing Snake Ropes, which was set on a remote island, my second novel, Cooking with Bones began with two sisters fleeing a futuristic city (called Paradon) who quickly found their way to a strange and remote village. So both of my first two novels were mainly set in insular locations which had their own rules, folklore, mythology and sense of community. In City of Circles, I wanted to invent a magical city which also had all of these things, but on a larger scale. I used more description for the city, as it was such a unique and remarkable place, full of strange characters and places. Even the houses had their own unique ‘atmospheres’ and the house that Danu squats in has its own narrative voice. It was great fun to consider what kind of character a house could be – as cities are crammed full of buildings as well as people I came to see the buildings and the city itself as having their own personalities. As well as being part of the setting in that they were interesting things for the main characters to look at and explore, they also became part of the story.

As someone who has lived in several different places and recently moved to Wellington, how has your own experience with cities and identity compared to Danu’s?

When I’d just started to write City of Circles, I left my home of 18 years, and decided to remain voluntarily homeless for a period of time. During the next two years I couldn’t settle anywhere, so I looked after other people’s homes and pets, even their holiday cottages, which were sometimes in isolated rural places and sometimes in villages, towns, and cities. I slept in many different beds and was quite envious of Danu owning her own mattress, even though the caravan it was in kept moving on. All the places I lived in or visited found their way into City of Circles, as aspects of the places the circus travelled through, and several cities (London, Chicago, Wellington to name only a few) added to the descriptions of the different areas and revolving circles within Matryoshka, the city she eventually remains in. When Danu fell in love with Matryoshka, she experienced it almost as a living and breathing place, filled with enchanting scents and intriguing secrets. While I was exploring many different ‘homes’ I deeply wished to find somewhere which called me to it. Somewhere to love. As it happens, it was a person, not a city, I fell in love with, and that’s how I came to move to Wellington. I followed my heart to a person, while Danu followed her heart to a city.

Several reviews have praised your treatment of grief in City of Circles. How did you approach this theme?

My father died suddenly while I was writing City of Circles, and just three months after his death, I came to New Zealand. Experiencing grief so far away from anyone who knew him was an isolating experience. When we’re not with people who also knew the person who died, because no one is talking about them, there are no new memories to be had. All I could do, while grieving at such a great distance was to pour my grief into this novel. To give it to Danu, as it was too hard a thing to carry alone. As Danu’s parents had died right at the beginning of the novel, I wrote about her grief at the same time as I experienced my own. The physical pain of grief is something that few people talk about, so I gave aspects of this to Danu. I had her describe watching someone die, which is also something that few people talk about. She ties her mother’s locket like a choker around her throat, and trusses her ankles with her father’s bootlaces. The pain, to her, is a constant reminder of the strength of her love, and the strength of her loss. When she finally faces her grief, she does so from a high rooftop, throwing lily petals into the sky, and letting the wind carry them away. She’s trying desperately to part with her sorrow, and let it fly from her. But the truth of grief is that it never goes away. We each have to find our ways of living alongside it. And that is what Danu does as well. Learning to live beside grief takes time and courage. Others are also affected by it, which we see in Morrie, a charismatic hunchback who is in love with Danu, though she can’t reciprocate.

You were recently involved in an event at the Post-Apocalyptic Book Club in London. How did this go, and how do you see your work in terms of the genre of dystopian and speculative fiction?

It was a lovely event – with a great chairperson who had prepared excellent questions about City of Circles in advance. She got me to talk about more things than I’d realised I could. The audience were also great – really interested in the process of ‘world building’ and inventing an imaginary city. I tend not to think too much about genre when I write – to me, the main thing is the characters, and their story, and the world they are in being believable. That said, speculative fiction is a broad term which spans a variety of genres such as fantasy, sci-fi, young adult fiction and literary fiction. To me, what speculative fiction means is that the author has been ‘speculating.’ Asking… what if? And then answering their question in the form of a story. What if… there was an undiscovered island off the edge of a map? (This was the question behind Snake Ropes.) What if… an old woman was several people, and not just one? (One of the questions within Cooking with Bones.) And what if… a city was built which was made out of revolving circles, like a clockwork toy… and what if… a grieving woman thought she was alone in the world, and then discovered she had a double… In terms of dystopias – they’re far more interesting to write about than utopias, because I don’t believe that utopias exist. I also like writing amoral characters, who are neither completely good nor totally bad, but somewhere ambiguous in between. Darkness is, to me, much more interesting than light.

Auē, by Becky Manawatu