“The heroes of war are publicly honoured, and their brave deeds are taught to children… (while) the heroes of peace most often go unrecognised.” So wrote Elsie Locke, in her introduction to Bread and Water, a memoir of New Zealand’s conscientious objectors.

For now more than a year, New Zealand has remembered the sacrifices and experiences of soldiers, nurses and civilians who fought in the First World War. Conscientious objectors, however, are less often spoken of, and uneasily sit on the boundary between these two groups. These were men who, through pacifist, religious, and/or moral conviction, refused to participate in the war. Although often overlooked in our cultural memory of New Zealand’s war experience, conscientious objectors, both around the world and in New Zealand, have certainly left traces in our history. Here at the library, we’re equipped with resources to help you discover the lives and thinking of these men – and of their families and those who their decisions affected.

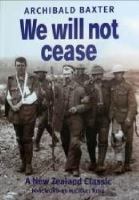

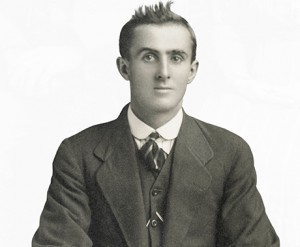

Perhaps the most well-known of New Zealand’s conscientious objectors is also known internationally. Archibald Baxter was outspokenly against war in the days leading up to conscription in New Zealand, was arrested unawares before being asked if he would sign up, and shipped from jail to jail before being sent to the trenches, to be punished with ‘Field Punishment Number One’, incarcerated in a mental hospital, and eventually sent home to New Zealand. He left a strong legacy of anti-militarism; in his son, Terence John, who was imprisoned as a conscientious objector in WWII, and in his matter-of-fact account of his experiences whilst imprisoned in his book We Will Not Cease. Written in 1939 in England, almost all copies of the book printed were destroyed in the Blitz, and it did not become well-known in New Zealand until the 1960s. Luckily, despite this the book is now available to borrow from the library. Since this time, it “has become a classic of New Zealand literature.”

Perhaps the most well-known of New Zealand’s conscientious objectors is also known internationally. Archibald Baxter was outspokenly against war in the days leading up to conscription in New Zealand, was arrested unawares before being asked if he would sign up, and shipped from jail to jail before being sent to the trenches, to be punished with ‘Field Punishment Number One’, incarcerated in a mental hospital, and eventually sent home to New Zealand. He left a strong legacy of anti-militarism; in his son, Terence John, who was imprisoned as a conscientious objector in WWII, and in his matter-of-fact account of his experiences whilst imprisoned in his book We Will Not Cease. Written in 1939 in England, almost all copies of the book printed were destroyed in the Blitz, and it did not become well-known in New Zealand until the 1960s. Luckily, despite this the book is now available to borrow from the library. Since this time, it “has become a classic of New Zealand literature.”

King and Country Call, by Paul Baker, is a second book about the experience not only of conscientious objectors in WWI, but also about conscription, how it was introduced to New Zealand, and its consequences. It is available to borrow, again from the Central Library.

Conscientious objectors’ lives and convictions are canvassed by the books above, and other titles in our library catalogue, but the details of their lives and beliefs, their principles in their own words, are often to be found in the details of life in archival sources. Army records and newspaper clippings give us another glimpse into conscientious objectors’ lives. PapersPast is an invaluable online, searchable database of New Zealand newspapers from 1839 until 1948. A search for ‘conscientious objectors’ or the name of a particular figure brings up a huge number of resources.

The National Archives, likewise, provide access to defence personnel files from WWI, which can be viewed online and include details of deployments, conduct and medical files – invaluable resources.

Both these websites, along with many other resources useful for researching our history such as NZHistory.net and Te Ara, can be accessed from the free internet computers at any Wellington City Library.

In Wellington, last year’s WW100 project honoured not only eight servicemen, and one nurse, but a conscientious objector born and bred in the region, Ernest Kilby of Island Bay. Ernest resisted conscription due to his Open Brethren Christian beliefs, and was imprisoned from 1917-1919. Ernest Kilby’s likeness and story were pasted up in Island Bay as part of the city’s war commemorations. His story, and background information, can be read on the council website. Accounts of Ernest’s conviction and various trials can also be read on the Papers Past online archive.

Sometimes forgotten, but worth remembering, the conscientious objectors of the First World War still leave their legacy. WWI was the first instance of conscription in New Zealand, and one with mixed results. The resistance of the men who refused it, and their articulate reasons for doing so, provide a counterpoint to our dominant cultural narrative of the war.